Brains. Brains. Put this trivia in your brains.

From their beginnings in Caribbean voodoo culture to a Brad Pitt blockbuster, the zombie has been reanimated many times over in the last couple centuries. Animal entrails have been eaten by eager extras, countless kids have been frightened out of their minds and Bill Murray even got to play a zombie.

With the updated and fully revised release of author and journalist Jamie Russell's "Book of the Dead: The Complete History of Zombie Cinema," HuffPost Entertainment spoke to Russell to learn a bit more about the phenomenon that's become ubiquitous in American culture in recent years.

When he began the first edition of this book, as Russell put it, "people weren't interested in zombies at all." He said it took him by complete surprise. At times his wife even threatened to turn him into a zombie. But now the zombie is unavoidable. Talking about how the zombie can serve as a "kind of a metaphor for the death we all face," Russell said: "No matter how hard you try to run away, it's always going to get you." In contemporary America, especially as Halloween quickly approaches, there's no escaping this monster.

Here are eight things you didn't know about zombie movies.

![TK TK gifs]() 1. The idea of zombies comes from Haitian voodoo and were popularized by a book called "The Magic Island."

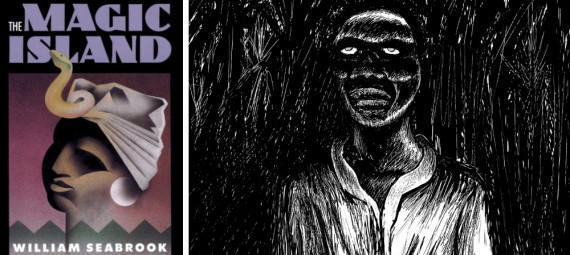

1. The idea of zombies comes from Haitian voodoo and were popularized by a book called "The Magic Island."

![141267431]()

The word "zombie" first made its way into The Oxford English Dictionary in 1819, but as Russell explains in "Book of the Dead," the first full introduction of "zombies" into the English-speaking world was an 1889 article in a Harper's Magazine called "The Country of the Comers-Back" by a journalist named Lafcadio Hearn. While learning the local customs of the Caribbean, Hearn came across a legend of "corps cadavres" which means "walking dead." Unfortunately, Hearn was unable to figure out exactly what these zombies were, a mystery that would eventually be solved by an American author named William Seabrook.

"The Magic Island" was written by Seabrook and was released in 1929. Seabrook discovered that the fear of "zombies" was tied to the practices of voodoo where it is possible for their idea of a soul to be removed and replaced by a god or sorcerer. As voodoo was deeply connected with the forced work and slavery of the people of the Caribbean, the main fear was that it'd be possible, even after death, for a sorcerer to reanimate your corpse to be an obedient drone, capable of continuing to work in the fields. Richer Haitian families would bury their dead in more secure tombs to eliminate the risk of the bodies being stolen and reanimated. They were not afraid of a zombie attack, they were afraid of becoming a zombie.

Russell told HuffPost: "From my point of view, as a kind of movie historian and anthropologist, the ground zero for the zombie really is 'The Magic Island' and the publication of that is really what brought the zombie into American popular culture ... This is certainly the arrival of the zombie myth in all its glory. The idea of dead men walking. The idea of dead men working in the cane fields."

Seabrook actually met "zombies" as a Haitian famer named Polynice introduced him to three workers who seemed "unnatural and strange" and "plodding like brutes, like automatons." Although Seabrook did not think they were actually the reanimated dead -- and instead either had a medical condition or were heavily drugged -- he could not fully explain away their existence. As a result, his tales took hold in American imaginations.

Image Left: Amazon. Image Right: WikiCommons.

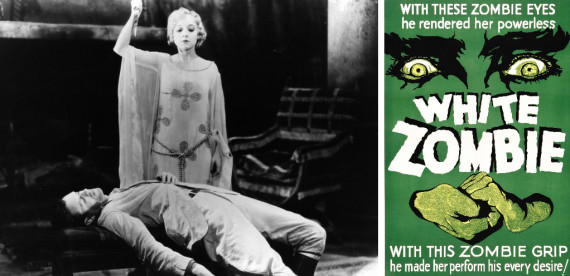

2. Zombie culture began taking off in the U.S. in the early 20th century, particularly with the film "White Zombie."

![169426048]()

"White Zombie" was released in 1932 and was directed by Victor Halperin. Bela Lugosi, who famously played Dracula the year before in 1931, starred as an evil voodoo master who takes over the body of a young woman.

R: "It was an independent movie, but 'White Zombie' was pretty huge ... 'White Zombie' is really interesting because she's a white zombie, a white woman whose kind of zombified. And she's not actually dead. And it's more a kind of hypnotized state."

In the 1936 sequel, "Revolt of the Zombies," the monster narrative began to adapt into something contemporary audiences are more familiar with.

R: "The followup movie was called 'Revolt of the Zombies' and that was kind of the first time it's not a solitary zombie. That's one of the first movies where it's like, 'Wow this is a big deal.'"

The next few decades brought dozens of mostly forgettable and cheaply made movies. Then George A. Romero's 1968 classic, "Night of the Living Dead," changed everything.

R: "A huge watershed moment in terms of it's the moment where the zombie myth changes, you certainly have the sense of it becoming this global apocalypse happening. Zombies go from being these Haitian slaves, a myth of slavery, into proper cannibals and that is the basis of the modern zombie myth. That they're not just dead but they want to eat you too ... "Revolt of the Zombies" is the first idea this can be a global phenomenon. And that expands in "Night of the Living Dead," the start of zombies as flesh eaters."

Image:

WikiCommons.

3. Zombies can be very cheap to create in movies and therefore there's a long history of terrible zombie movies being made. This affects the quality control of the genre.

![TK TK gifs]()

Creating a passable "zombie" monster wasn't too expensive as it's fairly easy to convey the idea that someone is a zombie. Low production cost studios would just churn these movies out. As Russell elaborated, "The movies that came out of the Poverty Row studios at that time, 'Voodoo Man' and stuff like that, these were all very cheap things." Compared to other monster movies, zombie movies were relatively easy to make.

R: "The reason why zombies appealed was because you could take actors and slap a bit of makeup on them and all they need to do is stretch their arms out and everybody will believe that they're a zombie. They might not be the most convincing zombies ever, but in terms of the mechanics of the genre, that's all that's really needed. Doesn't require any special effects. Say if you're going to make a werewolf movie, you'd need the transformation of someone turning into a werewolf. With zombies, you don't need to do that. Put some flour on their faces and make them stretch their arms out and lumber around a bit."

Casting a zombie movie was also easier than the other monster movies.

R: "The zombies weren't speaking parts which means you didn't have to pay the actors as much to be monsters ... If you are going to cast a vampire role in those days -- everybody had seen 'Dracula,' so everybody expects Dracula to have a certain menace and presence and have a certain Bela Lugosi role. If you're going to make a Frankenstein, a mad science monster created kind of movie, you want someone who has the soul of Boris Karloff who makes you feel compassion to this monster. With zombies nobody cared. It didn't matter. They were there just to be grasping hands and to grab people and drag them down to the depths. So that was very simple."

This cheapness didn't help the zombie become a "respected" monster and became closely tied to these B movies in the public's mind.

R: "There's no simple way of getting around that, in terms of quality control, the zombie genre really does suck."

4. There's no strong literary history for the genre and therefore the idea of what a zombie is very malleable and can change to reflect the fears of the time.

![166977815]()

Unlike "Dracula" and "Frankenstein," there isn't a clear source material for the zombie genre. Seabrook's work isn't recognized the same way the great monster fiction writers are and simply doesn't hold the same influence.

R: "The fact that there isn't an established literary heritage or canon behind it -- there's no Mary Shelley or Bram Stoker -- means that filmmakers felt like they could write the roles as they went along and no one would mind too much. There was the essential zombie myth of voodoo work. That lasted for a little while, but that quickly fell by the wayside. It didn't take too long for people to change it around and mix it up. By the time you get to Romero, then voodoo isn't really a part of this at all ... Suddenly the whole genre is evolved and it's happened again recently. Zombies used to be the monsters that come out of the graveyard and in the last 15 years or so they stopped being that. They're now metaphors of contagion and plague and viruses ... Most zombies these days aren't even dead, they're plague carriers."

The zombie myth regularly updates and adapts to the times. Whatever we're most deeply afraid of, the zombie can embody with their reanimated bodies.

R: "What's interesting about the zombie myth is just how much it evolves. If you go back to the original Haitian myth, the fear of the zombie isn't so much a fear of death, it's a fear that death might not be a release from slavery. The worst thing as a slave is imagining, 'After my death I might still be reanimated to continue working in the cane fields, that there is no escape.' And that changes once [the myth] comes to America and that idea of the zombie then becoming an image of death itself is something very powerful."

Although the zombie originally started as a fear of eternal slavery, the zombie can constantly update to take on contemporary issues.

R: "It's a very malleable and flexible monster. It's very good at reflecting. Horror is generally very good at reflecting the kind of anxieties and fears of the audience that's watching it at the time. [But] the zombie in particular, as it evolves so much over time, really reflecting different fears in different eras in really interesting ways. So certainly for the original readers of 'The Magic Island' it was very much a fascination in fear about Haiti, this island that america at the time had invaded and was occupying and it was a military occupation. For those early stories it was that. Later it became American race relations in society ... What I love about this monster, is that it is very good barometer of the times in which the movies are being produced."

Image Left: WikiCommons.

5. Due to the always changing idea of what a zombie is, Roger Ebert once witnessed a ton of very young children being dropped off to see "A Night of the Living Dead" by unknowing parents. Needless to say, the kids were terrified.

![2411955]()

For decades creature movies like "Creature from the Black Lagoon" or "Attack of the Crab Monsters" dominated horror cinema which led to a bit of confusion when the zombie changed so radically in 1968, with Romero's "Night of the Living Dead." Russell talked about

Roget Ebert's review of a screening of the movie as a funny instance of the public's initial confusion.

R: "Best of all is Roger Ebert's story of watching 'Night of the Living Dead' with a bunch of 7-year-olds at a Saturday matinee. They'd been dropped off while their parents when shopping -- the moms and dads assumed it was just another creature feature movie."

Here's an excerpt from Ebert's article describing the theater immediately following the ending:

The kids in the audience were stunned. There was almost complete silence. The movie had stopped being delightfully scary about halfway through, and had become unexpectedly terrifying. There was a little girl across the aisle from me, maybe nine years old, who was sitting very still in her seat and crying ... I felt real terror in that neighborhood theater last Saturday afternoon. I saw kids who had no resources they could draw upon to protect themselves from the dread and fear they felt.

6. In "Night of the Living Dead," the zombie extras were forced to eat actual animal entrails to make it look more real.

![TK TK gifs]()

When talking about random zombie trivia, Russell told of how Romero decided to go to a butcher and get real entrails for his zombie extras to eat.

R: "What I always loved about the Romero movies and in particular "Night of the Living Dead," what always amused me, was that the extras were so keen to be in a movie, they were willing to eat real entrails from the butcher shop. They shipped in this real stuff. The scene that Romero always refers to is the 'Last Supper,' where the young good-looking kids get barbecued in their truck as they're trying to escape from their farmhouse ... Not only do they get eaten, but Romero spends about five minutes of these zombie extras kind of munching down on these animal entrails. [I] always laugh at that a lot."

And apparently this sort of thing isn't too uncommon ...

R: "The entrails thing is funny, I love the idea how keen people are to be in the movies. That they're willing to do that kind of thing. Zombies cinema is full of these kind of cheap and cheerful productions like that. Just throw people together. I think that's a lot of the appeal."

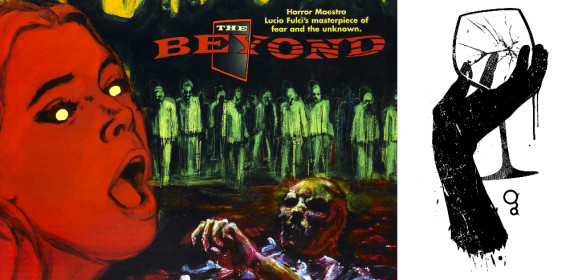

7. Classic zombie director Lucio Fulci would use homeless winos as zombies.

![506004441]()

Continuing the zombie trivia conversation, Russell mentioned that the legendary Lucio Fulci would use the homeless as his extras while directing "The Beyond" and "Zombi 2." As mentioned earlier, zombies films are known for their frugality and Fulci's films were no exceptions. "Cheap to employ and I guess they had the zombie stagger perfected!" Russell said.

As movie reviewer Chris McEneany explained in

AVForums:

Quite a few of his ambling zombie-targets, and that eerie assortment of desiccated corpses lying in the wastes of the Beyond, are actually local down-and-outs and homeless people lured in with the cheap promise of a meal and a few quid to get some more booze. You look at them –- they're not acting, are they?

Image Right: Flickr user gritphilm.

8. There's a movie called "Poultrygeist: Night of the Chicken Dead" that takes place in a sort of KFC built above a Native American battle ground.

![506004441]()

This movie came out in 2006 and according to the movie's

website, Stephen King called it "hilarious."

"There's an awful lot of bad movies," said Russell. Here's a list of a few other campy and terrible zombie movies Russell mentioned:

- "There's a great '60s movie called 'The Frozen Dead,' which is basically about Nazi zombies and the Fourth Reich being put into being by these reanimated zombie ghouls who've been kept in cryogenic suspension. Don Andrews plays a scientist whose trying to bring them back, but every time he resurrects them they're kind of falling apart mentally and unable to do very much in the way of recreating Hitler's vision."

- "If you have five minutes you should Google a trailer for something called 'O.C. Babes and the Slasher of Zombietown.' If you see the trailer then you'll understand. This is a movie that basically most of the zombie action recycles the zombies of "Night of the Living dead." Just reuses the footage which is bizarre.

- "There's something called 'The Curse of Pirate Death.' Which might be the worst zombie movie I've ever seen. Clearly shot cheaply in the hills of California somewhere. And it's a guy in a kind of jokester pirate outfit that is supposed to be a zombie who has come back for treasure that's been stolen. Basically [the pirate] just spends the movie chasing teens shouting "arghh where's my treasure?" and skewing them on his sword. The only moment of wit in the whole movie is when he discovers a swimming pool in someone's backyard and is really perplexed by it. He's like, 'What strange body of water is this, there's no sharks. This is great.' Then the movie just goes back to him chasing these poor kids around."

- "There's rat zombie movies. Something called 'Mulberry St,' which is basically set in Manhattan. [The movie is] rats kind of turning people into rat zombie hybrids."

Russell also has a few contemporary deep cut recommendations to watch on Halloween, those being "Pontypool," "The Battery," "The Dead," the remake of "The Crazies" and "REC."

But as Russell admitted about the movies of the zombie genre, "Some are more amazing to read about and talk about than actually watch."

Images: WikiCommons.

The updated version of "Book of the Dead" is out October 14.

![TK TK gifs]() All other images Getty unless otherwise noted.

All other images Getty unless otherwise noted.