"Good artists copy," goes the saying, supposedly uttered by Picasso, "and great artists steal." The Japanese artist Takashi Murakami seems to have taken the quote as a directive. His latest, psychedelic exhibit, "In the Land of the Dead, Stepping on the Tail of a Rainbow," borrows liberally from the past, running ancient art and architecture through Murakami's signature filter, a high-low, cross-cultural aesthetic he calls "Superflat."

![takashi murakami rashomon gate]()

The show's most striking piece, "Bakuramon," simulates a legendary gate that once led to the capital city of Heian-kyo (modern-day Kyoto) in 10th century Japan. Placed strategically in the sightline of a viewer turning the corner inside New York's Gagosian Gallery to enter the show, this gate incorporates wood and stone, and rises nearly to the rafters. In the blank gallery, the raw brown construction looms like a shipwreck on bleached sand. The original gate was known as Rashomon, and served as the setting for the eerie short story underpinning the famous Akira Kurosawa movie of the same name. Murakami's version marks the entrance to another strange world: through the gate grins a skull, rendered in the manic colors of modern Japanese otaku culture.

It's a fitting opener. In the gallery notes, Murakami links the shifting history of the gate with what he calls a "recurring theme of misinterpretation in my work." Heian-kyo was modeled after the capital of Tang dynasty China, where walls protected the gated city from foreign invaders. In Japan, the same architecture lost meaning. On an island nation "where there were no real external threats," Murakami writes, "functionality" disappeared. "Rather than surrounding the capital, the walls only flanked the gate -- purely as a formal element -- and the gate therefore became merely symbolic."

Rashomon was destroyed by storms twice. By the famine of the 12th century, the gate had become a dumping ground for dead bodies. Kurosawa fans know the setting in this incarnation, a spooky place where a man might steal from a near-dead woman, as happens in the movie.

Darkness attends Murakami's gate too. To its right, two demons stand at attention. Their names are "Embodiment of 'A,'" and "Embodiment of 'Um,'" a nod to the first and last letters of the Sanskrit alphabet (as demonstrated in the popular mantra, Om, which is a simplified spelling of Aum). Murakami's demons symbolize the start and end of the universe. They also turn a convention on its head. "Normally, a temple gate would be flanked and guarded by devas," Murakami writes, using the Sanksrit word for deity. "But Bakuramon, in keeping with the symbolism of its deterioration and harboring of demons, is guarded by these two."

![takashi murakami]()

Shuffling demons and deities is classic Murakami, the kind of disturbing move he seemed to be shying away from in recent years."The gate itself is a multi-layered adaption," he writes, a conflation of the "8th century gate built based on the Chinese model, the 14th century fables and legends, the modern fiction writer's interpretation of the legends, the filmmaker's re-envision of the fiction, and my own adaptation of the setting of the film. Misinterpreted as a temple gate rather than the entrance to a city, it also conflates Buddhism, Shintoism, and animism, in line with the Japanese propensity to mix and match elements of different religions and spiritualities."

And mix and match he does. On a far wall, three paintings reimagine the Buddhist concept of arhats, or enlightened beings. Since the 2011 disasters in Japan, Murakami has explored the country's conversion of arhats into saintlike figures, with powers that cure specific ills. His take on them, a series of eye-like spheres, reflects a fascination with science fiction. "People require a narrative in one form or another -- whether it be religion or sci-fi -- in order to cope with living on in the face of such a massive loss and sense of helplessness," he writes.

![takashi murakami]()

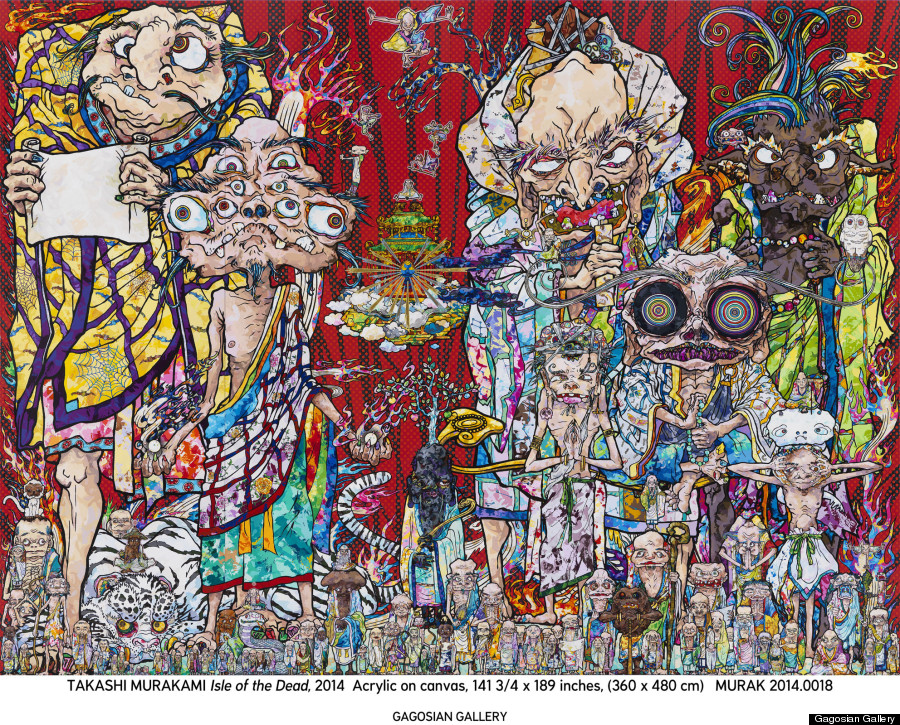

Meanwhile, the skull that confronts a viewer on a first trip through Bakuramon belongs to yet another reimagining, a mural inspired by the 18th century painting "Immortals" by Soga Shohaku. A provocateur in his own time, Shohaku twisted a popular Taoist archetype -- hermits with magical powers -- into grotesque forms. In Murakami's hands, the immortals are positively torqued, with wavy features and long, witchlike nails.

![takashi murakami]()

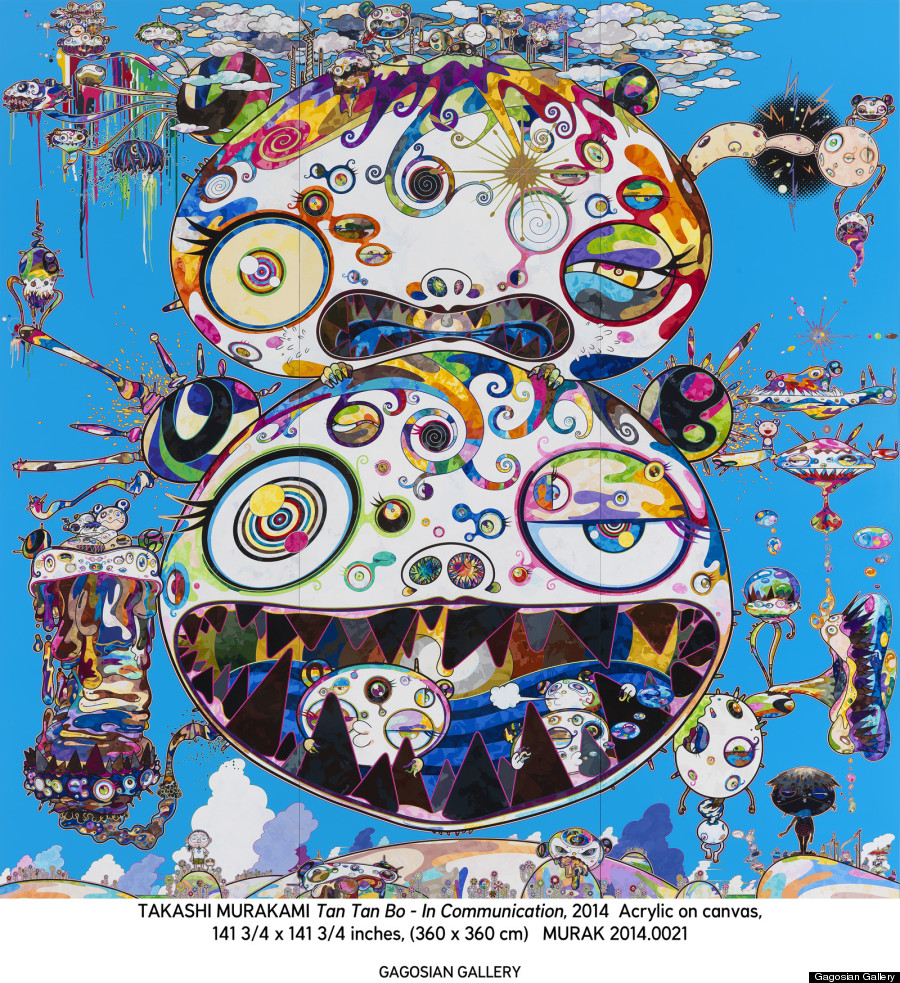

In the gallery's smaller halls, more cross-breeding awaits. Large canvases gleam with the bright colors of the Superflat world, and shiny sculptures evoke gilded Chinese ornamentation. But form doesn't necessarily match content. Whereas the paintings recall historical motifs, the sculptures evoke the concerns of the Internet age, from a man in round hipster spectacles -- meant to represent Murakami himself -- to a cheerful, abstract dog. Both are seated on platforms recalling Buddhist iconography.

![takashi murakami sculpture]()

![takashi murakami]()

It's hard to picture a better welcome mat for the show than the stone path under Bakuramon. To pass through its precursor, Rashomon, was to submit to the dream of Heian-kyo. Murakami's gate offers another journey, he writes, "from the outside to the inside, this side to that, this culture to the other."

Scroll down for more images from "In the Land of the Dead, Stepping on the Tail of a Rainbow."

![takashi murakami painting]()

![takashi murakami painting]()

![takashi murakami painting]()

![takashi murakami sculpture]()

The show's most striking piece, "Bakuramon," simulates a legendary gate that once led to the capital city of Heian-kyo (modern-day Kyoto) in 10th century Japan. Placed strategically in the sightline of a viewer turning the corner inside New York's Gagosian Gallery to enter the show, this gate incorporates wood and stone, and rises nearly to the rafters. In the blank gallery, the raw brown construction looms like a shipwreck on bleached sand. The original gate was known as Rashomon, and served as the setting for the eerie short story underpinning the famous Akira Kurosawa movie of the same name. Murakami's version marks the entrance to another strange world: through the gate grins a skull, rendered in the manic colors of modern Japanese otaku culture.

It's a fitting opener. In the gallery notes, Murakami links the shifting history of the gate with what he calls a "recurring theme of misinterpretation in my work." Heian-kyo was modeled after the capital of Tang dynasty China, where walls protected the gated city from foreign invaders. In Japan, the same architecture lost meaning. On an island nation "where there were no real external threats," Murakami writes, "functionality" disappeared. "Rather than surrounding the capital, the walls only flanked the gate -- purely as a formal element -- and the gate therefore became merely symbolic."

Rashomon was destroyed by storms twice. By the famine of the 12th century, the gate had become a dumping ground for dead bodies. Kurosawa fans know the setting in this incarnation, a spooky place where a man might steal from a near-dead woman, as happens in the movie.

Darkness attends Murakami's gate too. To its right, two demons stand at attention. Their names are "Embodiment of 'A,'" and "Embodiment of 'Um,'" a nod to the first and last letters of the Sanskrit alphabet (as demonstrated in the popular mantra, Om, which is a simplified spelling of Aum). Murakami's demons symbolize the start and end of the universe. They also turn a convention on its head. "Normally, a temple gate would be flanked and guarded by devas," Murakami writes, using the Sanksrit word for deity. "But Bakuramon, in keeping with the symbolism of its deterioration and harboring of demons, is guarded by these two."

Shuffling demons and deities is classic Murakami, the kind of disturbing move he seemed to be shying away from in recent years."The gate itself is a multi-layered adaption," he writes, a conflation of the "8th century gate built based on the Chinese model, the 14th century fables and legends, the modern fiction writer's interpretation of the legends, the filmmaker's re-envision of the fiction, and my own adaptation of the setting of the film. Misinterpreted as a temple gate rather than the entrance to a city, it also conflates Buddhism, Shintoism, and animism, in line with the Japanese propensity to mix and match elements of different religions and spiritualities."

And mix and match he does. On a far wall, three paintings reimagine the Buddhist concept of arhats, or enlightened beings. Since the 2011 disasters in Japan, Murakami has explored the country's conversion of arhats into saintlike figures, with powers that cure specific ills. His take on them, a series of eye-like spheres, reflects a fascination with science fiction. "People require a narrative in one form or another -- whether it be religion or sci-fi -- in order to cope with living on in the face of such a massive loss and sense of helplessness," he writes.

Meanwhile, the skull that confronts a viewer on a first trip through Bakuramon belongs to yet another reimagining, a mural inspired by the 18th century painting "Immortals" by Soga Shohaku. A provocateur in his own time, Shohaku twisted a popular Taoist archetype -- hermits with magical powers -- into grotesque forms. In Murakami's hands, the immortals are positively torqued, with wavy features and long, witchlike nails.

In the gallery's smaller halls, more cross-breeding awaits. Large canvases gleam with the bright colors of the Superflat world, and shiny sculptures evoke gilded Chinese ornamentation. But form doesn't necessarily match content. Whereas the paintings recall historical motifs, the sculptures evoke the concerns of the Internet age, from a man in round hipster spectacles -- meant to represent Murakami himself -- to a cheerful, abstract dog. Both are seated on platforms recalling Buddhist iconography.

It's hard to picture a better welcome mat for the show than the stone path under Bakuramon. To pass through its precursor, Rashomon, was to submit to the dream of Heian-kyo. Murakami's gate offers another journey, he writes, "from the outside to the inside, this side to that, this culture to the other."

Scroll down for more images from "In the Land of the Dead, Stepping on the Tail of a Rainbow."