We've all heard recreational hallucinogen users describe their trips as "consciousness expanding," and according to some new research, this poetic description may have a scientific basis.

Using fMRI imaging from healthy participants who ingested psilocybin, the active ingredient in hallucinogenic "magic" mushrooms, researchers from Imperial College London found that the drug caused brain regions that are typically disconnected to communicate with each other.

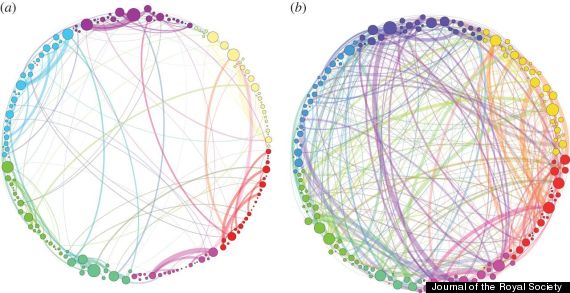

In a normal brain state, there's little cross-linking between different networks. But researchers found that on the psilocybin, the networks begin cross-linking all over the place. And these new connections weren't random. "It not so much that the number of connections are increased but rather that the connectivity pattern is different in the psychedelic state," Paul Expert, the study's lead author, wrote in an email to The Huffington Post.

That corroborates some of the common effects of psilocybin reported by users, such as new insights and realizations, synesthesia and nonlinear thinking.

Expert and colleagues used a new technique for network modeling, which is designed to look at network connectivity across the brain, rather than isolated systems or chemicals. The researchers compared the fMRI scans of the people who had taken psilocybin to fMRI data from 15 healthy individuals who had taken a placebo. Specifically, they were looking at functional connectivity -- the communication between different brain regions that share functional properties.

While a simple reading of the data would suggest that psilocybin is simply relaxing constraints on brain function and improving cognitive flexibility, it's a bit more complicated, Expert says.

"The brain does not simply become a random system after psilocybin injection, but instead retains some organizational features, albeit different from the normal state," Expert and his team wrote in the report. "Functional connections support cycles that are especially stable and are only present in the psychedelic state."

![mushrooms]()

Functional connectivity of a normal brain (left), compared to a brain on psilocybin.

"We find that the psychedelic state is associated with a less constrained and more intercommunicative mode of brain function, which is consistent with descriptions of the nature of consciousness in the psychedelic state," Expert and colleagues conclude.

Previous research on psychedelics from Imperial College London found that people on psilocybin had brain activity patterns more commonly associated with dreaming and heightened emotional functioning. In a Slate article on the finding, researcher Robin Carhart-Harris explained that when the emotion system is activated, the brain's "ego system," from which we get a sense of self, quiets down.

"Evidence from this study, and also preliminary data from an ongoing brain imaging study with LSD, appears to support the principle that the psychedelic state rests on disorganized activity in the ego system permitting disinhibited activity in the emotion system," Carhart-Harris wrote in Slate. "And such an effect may explain why psychedelics have been considered useful facilitators of certain forms of psychotherapy."

Expert's research is part of a larger effort to understand how psychedelics work and what their potential psychiatric applications might be. So far, the growing body of research has made some promising findings. A 2012 study found that psilocybin might be an effective intervention for depressive thinking, while research published earlier this year found LSD psychotherapy to be effective in easing end-of-life anxiety among patients suffering from terminal illness. Research being conducted on ayahuasca -- a potent hallucinogen, derived from the compound DMT, which has been used as a healing tool in Amazonian shamanism for hundreds of years -- is being studied as a potential treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder, addiction and other conditions.

Expert's research itself could be an important step towards devising psilocybin-assisted therapy for treating chronic depression.

"One of the characteristics of the depressed brain is that it gets stuck in a loop, you get locked into repetitive and negative thoughts," Expert told HuffPost. "An analogy is a particle stuck in a deep minimum in an energy landscape and is stuck there. The idea is that using psilocybin might help break the loop, change the patterns of functional connectivity in the brain, or in the analogy of the particle, give it enough energy so that is can escape from its minimum and explore the rest of the energy landscape."

CORRECTION: An image caption in an earlier version of this story stated that the image on the right was that of a normal brain, but it is the image on the left. We regret the error.

Using fMRI imaging from healthy participants who ingested psilocybin, the active ingredient in hallucinogenic "magic" mushrooms, researchers from Imperial College London found that the drug caused brain regions that are typically disconnected to communicate with each other.

In a normal brain state, there's little cross-linking between different networks. But researchers found that on the psilocybin, the networks begin cross-linking all over the place. And these new connections weren't random. "It not so much that the number of connections are increased but rather that the connectivity pattern is different in the psychedelic state," Paul Expert, the study's lead author, wrote in an email to The Huffington Post.

That corroborates some of the common effects of psilocybin reported by users, such as new insights and realizations, synesthesia and nonlinear thinking.

Expert and colleagues used a new technique for network modeling, which is designed to look at network connectivity across the brain, rather than isolated systems or chemicals. The researchers compared the fMRI scans of the people who had taken psilocybin to fMRI data from 15 healthy individuals who had taken a placebo. Specifically, they were looking at functional connectivity -- the communication between different brain regions that share functional properties.

While a simple reading of the data would suggest that psilocybin is simply relaxing constraints on brain function and improving cognitive flexibility, it's a bit more complicated, Expert says.

"The brain does not simply become a random system after psilocybin injection, but instead retains some organizational features, albeit different from the normal state," Expert and his team wrote in the report. "Functional connections support cycles that are especially stable and are only present in the psychedelic state."

Functional connectivity of a normal brain (left), compared to a brain on psilocybin.

"We find that the psychedelic state is associated with a less constrained and more intercommunicative mode of brain function, which is consistent with descriptions of the nature of consciousness in the psychedelic state," Expert and colleagues conclude.

Previous research on psychedelics from Imperial College London found that people on psilocybin had brain activity patterns more commonly associated with dreaming and heightened emotional functioning. In a Slate article on the finding, researcher Robin Carhart-Harris explained that when the emotion system is activated, the brain's "ego system," from which we get a sense of self, quiets down.

"Evidence from this study, and also preliminary data from an ongoing brain imaging study with LSD, appears to support the principle that the psychedelic state rests on disorganized activity in the ego system permitting disinhibited activity in the emotion system," Carhart-Harris wrote in Slate. "And such an effect may explain why psychedelics have been considered useful facilitators of certain forms of psychotherapy."

Expert's research is part of a larger effort to understand how psychedelics work and what their potential psychiatric applications might be. So far, the growing body of research has made some promising findings. A 2012 study found that psilocybin might be an effective intervention for depressive thinking, while research published earlier this year found LSD psychotherapy to be effective in easing end-of-life anxiety among patients suffering from terminal illness. Research being conducted on ayahuasca -- a potent hallucinogen, derived from the compound DMT, which has been used as a healing tool in Amazonian shamanism for hundreds of years -- is being studied as a potential treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder, addiction and other conditions.

Expert's research itself could be an important step towards devising psilocybin-assisted therapy for treating chronic depression.

"One of the characteristics of the depressed brain is that it gets stuck in a loop, you get locked into repetitive and negative thoughts," Expert told HuffPost. "An analogy is a particle stuck in a deep minimum in an energy landscape and is stuck there. The idea is that using psilocybin might help break the loop, change the patterns of functional connectivity in the brain, or in the analogy of the particle, give it enough energy so that is can escape from its minimum and explore the rest of the energy landscape."

CORRECTION: An image caption in an earlier version of this story stated that the image on the right was that of a normal brain, but it is the image on the left. We regret the error.