The first Ebola patient to be diagnosed in the U.S. died Wednesday. Three days earlier, government health officials in Sierra Leone reported 121 Ebola deaths in a single day. But Western media made little mention of the latter.

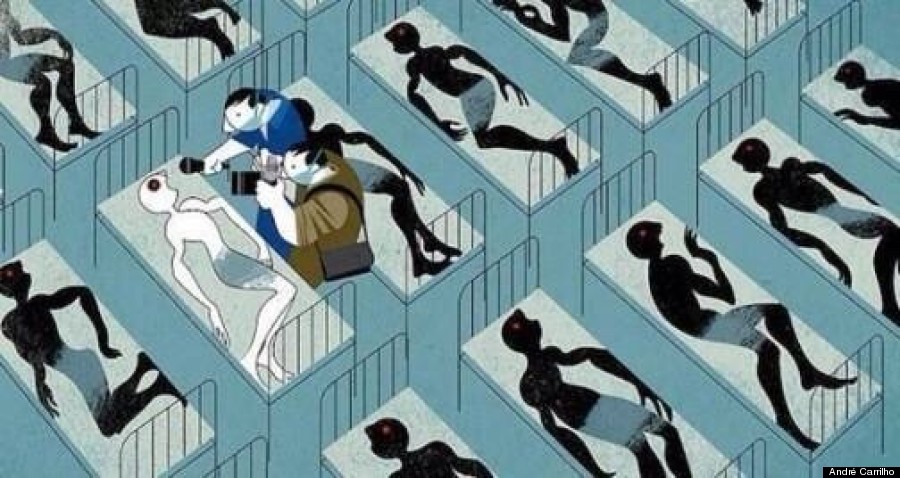

A new illustration from frequent Vanity Fair contributor André Carrilho puts that into perspective.

(Story continues below)

![andré carrilho ebola]()

Until American doctors treating patients with Ebola in West Africa were diagnosed with the disease, the current Ebola outbreak has been largely faceless, mainly about statistics and if and when the virus would spread to American soil.

Carrilho told The Huffington Post he created the illustration to show how the media "seems to treat epidemics differently, depending on where they occur, and to whom."

"I think unfortunately, in the Western media, there are first-world diseases and third-world diseases, and the attention devoted to the latter depends on the threat they pose to us, not on a universal measure of human suffering," he said. "A death in Africa, or Asia for that matter, should be as tragic as a death in Europe or the USA, and it doesn’t seem to be."

Since the first cases of the current Ebola outbreak were reported in March, 3,865 people have died of the disease in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The mortality rate for the disease averages around 50 percent, the World Health Organization notes, and there are currently no licensed Ebola vaccines.

Two American aid workers who survived the disease were given the experimental drug ZMapp for treatment. It is unknown if the drug helped in their recovery process, but the decision to administer the drug to the two victims was seen as controversial because African victims of the disease were not given the same opportunity for treatment.

Carrilho says this difference in treatment and media coverage shifts the paradigm.

"If an epidemic breaks out in the USA or Europe, suddenly the reporting is more engaged. This gives rise to a few side effects," he said. "The 'us versus them' relationship shifts from detachment to fear of incoming immigrants from affected countries, and in both race and nationalism have an active part."

If Carrilho could see one change in the way the outbreak and public health are discussed, he says, it would be to tack on more global perspective.

"I would like to hear from the people who are affected everywhere," he told HuffPost. "I would like to feel that everyone’s voices are more equally heard, even if they speak a language that is not mine."

A new illustration from frequent Vanity Fair contributor André Carrilho puts that into perspective.

(Story continues below)

Until American doctors treating patients with Ebola in West Africa were diagnosed with the disease, the current Ebola outbreak has been largely faceless, mainly about statistics and if and when the virus would spread to American soil.

Carrilho told The Huffington Post he created the illustration to show how the media "seems to treat epidemics differently, depending on where they occur, and to whom."

"I think unfortunately, in the Western media, there are first-world diseases and third-world diseases, and the attention devoted to the latter depends on the threat they pose to us, not on a universal measure of human suffering," he said. "A death in Africa, or Asia for that matter, should be as tragic as a death in Europe or the USA, and it doesn’t seem to be."

Since the first cases of the current Ebola outbreak were reported in March, 3,865 people have died of the disease in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The mortality rate for the disease averages around 50 percent, the World Health Organization notes, and there are currently no licensed Ebola vaccines.

Two American aid workers who survived the disease were given the experimental drug ZMapp for treatment. It is unknown if the drug helped in their recovery process, but the decision to administer the drug to the two victims was seen as controversial because African victims of the disease were not given the same opportunity for treatment.

Carrilho says this difference in treatment and media coverage shifts the paradigm.

"If an epidemic breaks out in the USA or Europe, suddenly the reporting is more engaged. This gives rise to a few side effects," he said. "The 'us versus them' relationship shifts from detachment to fear of incoming immigrants from affected countries, and in both race and nationalism have an active part."

If Carrilho could see one change in the way the outbreak and public health are discussed, he says, it would be to tack on more global perspective.

"I would like to hear from the people who are affected everywhere," he told HuffPost. "I would like to feel that everyone’s voices are more equally heard, even if they speak a language that is not mine."