Kathleen Hanna exploded onto the punk rock scene in the early 1990s, aiming to transform a music world dominated by men into a platform for feminists with a voice. "Go back.. back, back," she would bellow at male audience members from the stage of Bikini Kill shows, ushering women and girls to the front of her raucous performances. It was all part of the riot grrrl movement she helped create -- a subculture birthed in Olympia, Wash., that combined art and activism to address issues like gender-based violence, racism and homophobia.

But after more than a decade leading bands like Bikini Kill and Le Tigre, and speaking out against a media culture that continuously misunderstood third-wave feminism, Hanna stepped out of the spotlight. She was abruptly diagnosed with late-stage Lyme disease in the mid-2000s, a condition that left her battling a myriad of painful, nonspecific symptoms. So, with the riot grrrl phenomenon already splintered, Hanna left the music world to focus on her health.

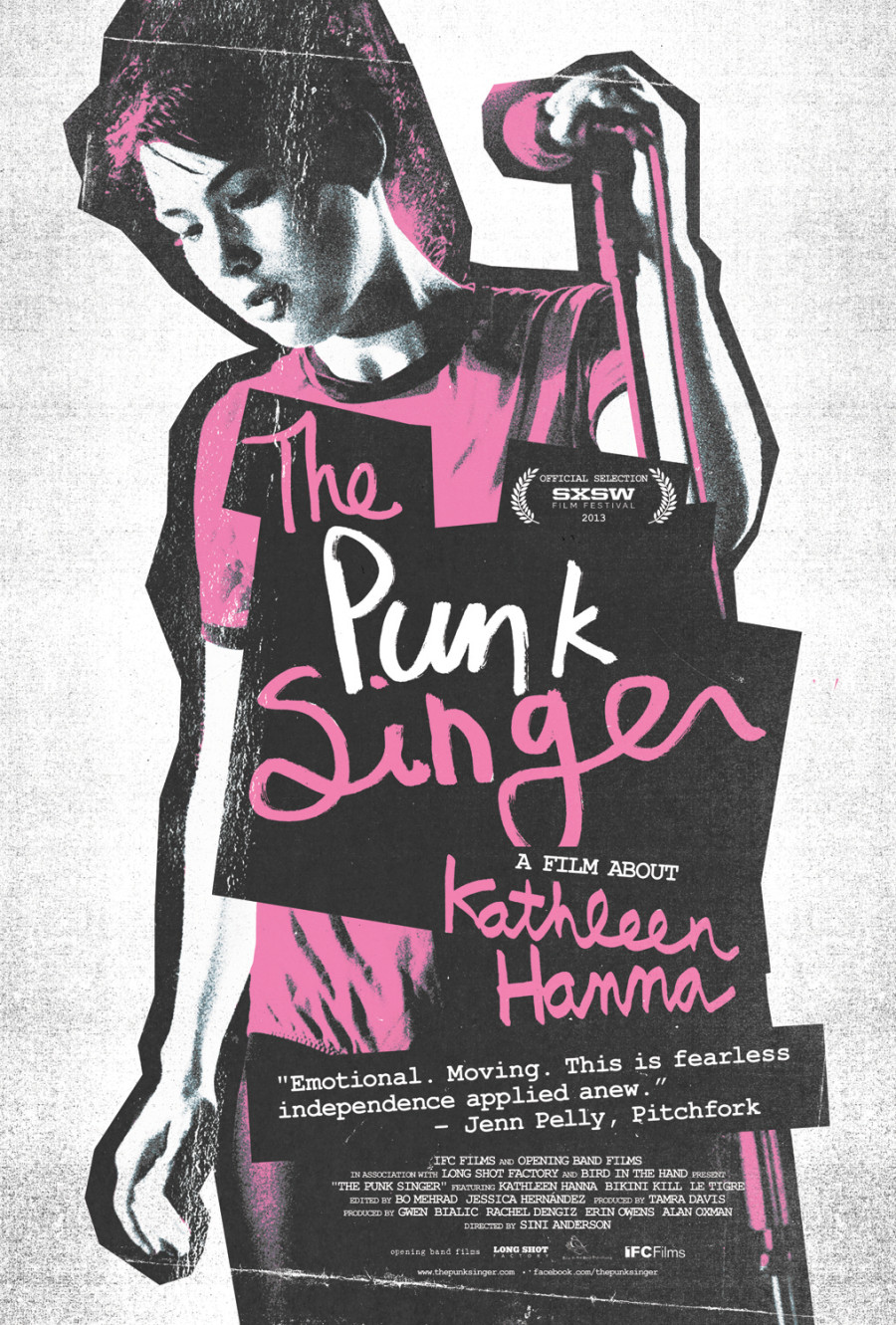

Fast forward to 2013, and Hanna is, in a word, back. Back with a new band (The Julie Ruin), a new album and a new documentary based on her life. The film, titled "The Punk Singer," outlines the years before and after her departure from the stage, following her early years working in domestic violence shelters and strip clubs to her marriage to Beastie Boys singer Adam Horovitz to her struggles with Lyme disease treatments today.

We had the chance to chat with Hanna ahead of the premier of the documentary, directed by Sini Anderson and featuring the likes of Kim Gordon, Joan Jett, and Carrie Brownstein. Here's what the singer had to say about Pussy Riot, Fred Flintstone and the age of the internet.

![kathleen hanna]()

Kathleen Hanna. Photo Courtesy of Lindsay Brice. An IFC Films release.

One of the things that struck me about the documentary was the negative relationship you guys had with the media in the 1990s. [Bikini Kill led a media blackout in 1993 as a result of tense relations with news organizations.] Obviously, something has changed, otherwise I wouldn't have the chance to talk to you! So what's different?

Right. I think people are asking better questions. They're being more respectful. I'm seeing that a lot of young, feminist punk rockers have grown up and become journalists. Thank god! It's been pretty great. You know, every once in a while there's that sexist interviewer guy who wants to talk to me about my husband, and doesn't want to talk to me about my record. But today's been great.

Do you feel like that misunderstanding you experienced in the 1990s has disappeared for the most part?

Yeah. I also feel like I'm older, so if I get asked questions I don't want like, I can just pass on them. There was not buffer when I was in Bikini Kill. We didn't have a manager or a publicist. We often times didn't even have a roadie. So there was no buffer between us and the public, or us and fanzine writers. Because it wasn't just the mainstream press that was sexist. People found out I worked as a stripper and that's all they wanted to talk about. Or all they wanted to talk about was gender. We were a radical feminist band, and I was fine talking about gender, but I also wanted to talk about songs at some point. That really never happened. Then the riot grrrl thing was just, "Baby barrettes and sexy young girls. Their feminism is ridiculous. They've all been sexually abused and hate men." That was the media narrative. I think that's definitely changed and people have a real kind of respect now for what we did. I remember thinking history is going to be on our side. And I was right.

Now I give lectures and people listen to what I have to say and ask me great questions. They come up after and say that they feel really inspired. I'm not getting the shit anymore. They don't think, "You're a man-hating bitch." And members of my own community aren't mad that I'm getting more attention than other people. I'm older, so I'm also like, I fucking deserve the attention! I worked my ass off. I deserve to have a movie made about me. I deserve to write a record about whatever I want. You know what I mean? Why the fuck not?

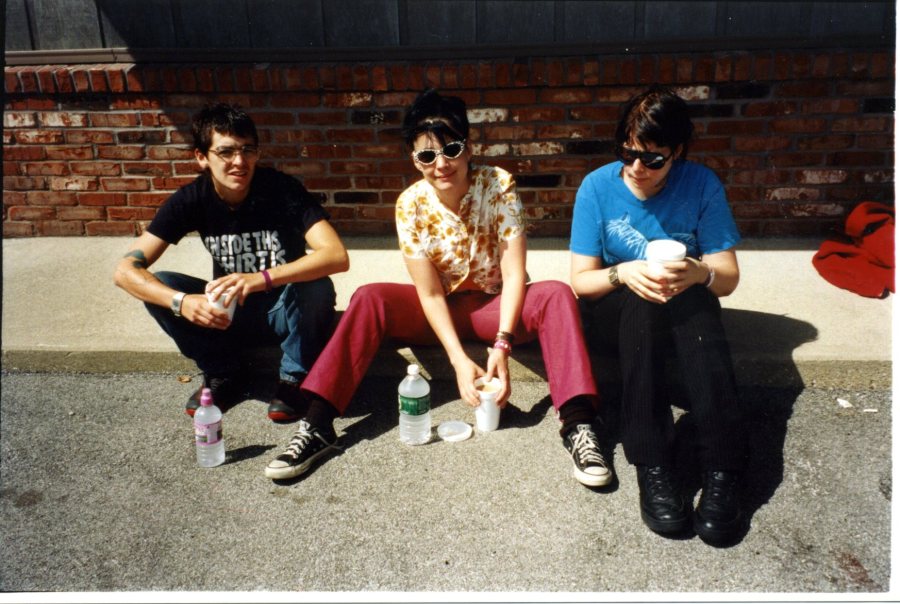

![5]()

Le Tigre drinking coffee. Photo Courtesy of Dusty Lombard. An IFC Films release.

You have quite the legacy. When I think about riot grrrl, one of the things I remember is Zine culture. And I think about how you almost did the internet before the internet was cool. You grasped the connective, DIY power of Tumblr and Twitter before any of these things existed. Does this thought ever cross your mind?

You know, for me, social media is really problematic. For somebody in a band, it's like this extra, unpaid job. To be perfectly honest, it's like you're expected to have an Instagram, Tumblr, everything. You're expected to be constantly giving people this information. The other day I was supposed to blog about how we were on the radio -- on WNYC -- and I was just so exhausted that I was just like, I can't get on the internet right now, I have other shit to do in real life. Sometimes I get really into it though; really into fucking around on my blog. And then sometimes I really just want to like... not check my email! [Laughs] You know what I mean? And not be doing all that.

But, when I think back to the '90s, I think we would totally have been all over that shit. We would have been tumbling and doing all this kind of stuff. A lot of people ask me the question, "Would riot grrrl exist in the internet age?" And, of course, I'm not sure. Because there's so much stuff on the internet. Everybody goes down a rabbit hole. I go on Facebook and then I click on something and I click on something and I click on something. I forget...

What you went online for in the first place?

Yeah! And I feel like the thing that was amazing about the '90s and the pre-internet era was that we wrote each other letters. We decorated them. We made each other packages. And it was really special when you got something from a friend. It was really special when you got a fan letter. One of my biggest regrets, actually, is that I had like three garbage bags of fan mail. It was my job in the band -- Tobi did some -- to answer our mail. Our mail was really intense. Really, really intense. I had people coming out to me personally as sexual abuse survivors, or saying, "I'm gay, and I've been kicked out of my family and social group." They were trusting me with this information when they didn't even trust their friends with it, or their parents. That, to me, was a huge part of the job. And I'm really sorry that I got rid of that stuff. But it was people's personal information and it's not the kind of thing you can put in an archive without asking each and every single person.

But yeah, three garbage bags. And I only started keeping them at a certain point. That just wouldn't happen now. Now it's emails. I think that when you have to sit down and write a letter to somebody you think about it more. You have more time, because you have to write it, put it in an envelope, address it, stamp it, go somewhere and mail it. I got a lot of amazing mail and I got a lot of hate mail. Today on the internet people can write whatever they want, though, about the Dum Dum Girls or whomever.

![kathleen]()

Kathleen Hanna. Photo Courtesy of Dusty Lombard. An IFC Films release.

Or the Chvrches' singer, Lauren Mayberry [who wrote an op-ed for The Guardian titled "I Will Not Accept Online Misogyny"].

Right! Exactly. It's like anybody can go online and write this messed up shit and be totally anonymous. They aren't all these steps they have to take. I don't know if you ever watch "The Flintstones"?

[Laughs] Yeah, sure.

Ok, so you know when Fred Flintstone writes the evil letter to [his boss] Mr. Slate? When Fred Flintstone is pissed off and he goes and he puts it in the box, but then later he tries to get it out? It's like that. I feel like a lot of people would be Fred Flintstone trying to get the thing out. They'd be like, "That was stupid. I was just really pissed in that moment." You know what I mean? You had to really hate me then, to send me a package with a bunch of porn and hate mail in it.

Bikini Kill also had some pretty vocal critics who would show up at your shows and stand in front of you as you performed.

Yup.

So there is this strange difference between the confrontational critiques before the internet and this anonymous negativity that doesn't really have a face or anything tangible to attach to it. It also becomes very apparent, to people who aren't fans of the band that this negativity exists.

You know, I hadn't really heard of the band before the op-ed. I read the piece and that's what got me interested in the music. To me, it was this really positive thing. I was on a radio show in England and she was on it, and we talked about it. It was really great. I had said in an interview a really long time ago to just not read [hate mail]. Don't look for stuff. We already have enough hateful shit in our brain.

It's a thing thing with the internet -- and even pre-internet. There were a lot of people during riot grrrl that just really hated me. And it really hurt when it was other women. It's fine to have arguments and divisiveness within a movement. I think that's actually beneficial. But when there are people who are just shaming and blaming you, or using political rhetoric in an angry way just because they're pissed they want to be where you are. They want to be in a band or they want to be a leader, or whatever. Every kind of bad thing I had in my head I had said to me. I really had to get rid of that. Any negative thing you can think of about your body, or how you sing if you're a singer. You know, this one lyric was stupid. Someone's going to write that and reinforce that in your head. We shouldn't have to just deal with street harassment or these horrible comments on the internet. She's right. But the fact of the matter is, it's there. So I choose not to read it. I choose to ignore. Because my friends are not like that. And I get to hang out with people who don't say mean comments like that! [Laughs]

![11]()

Kathleen Hanna with fans in Kyoto, Japan. Photo courtesy of Dusty Lombardo. An IFC Films release.

And then you fast forward. Pussy Riot. Did you envision that 15 years after Bikini Kill, women in Russia would be dressed in ski masks and neon clothing, using riot grrrl lyrics to combat authoritarianism in Russia?

No, absolutely not! I think it's the same way Ian MacKaye felt about straight edge. He was just writing shit in his own community for his friends. We were just doing it for our friends. We were inspired by people like G.B. Jones and homocore. Stuff that was coming out of Canada. Our friend Donna Dresch. People from San Francisco who were writing fanzines about being queer. That's what was inspiring us. And telling us that it's ok to write about what we were thinking about. And put it out in our scene.

And we were most worried about the guys in our scene. Because the first response we got was from these animal rights activists in our scene who wrote this really hateful fanzine that was all about this woman being raped and murdered and at the end you find out it's not a woman, it's a cat. And that was their response. That animal rights were more important. Trying to have a dialogue with those guys -- that's what we were thinking of. We weren't thinking, "This is the beginning of a movement. Then the Pussy Riot girls are going to get jailed and be challenging Putin." Like, totally not thinking of that. Of course not.

So when you look at the documentary after all the interviews and filming you went through, is there anything you think the film left out? Anything that you wish it would have covered from your life?

The thing that was left out... the thing that I talked about a lot and that I was really happy that I talked about was kind of what I saw as the failures of riot grrrl. And the stuff that I'm telling you now. That there was hatred towards me and my band that wasn't just from angry men. There was this whole faction of people who were mad at me because I was the wrong kind of feminist. There was a lot of stuff about race and class that was left out of the discussion or was discussed in a completely different way or inappropriate way in factions of Riot Grrrl. And I talked about that during filming and finally felt safe talking about it. But the good news is, there's a movie being made about Riot Grrl too, and I said all those things in that too.

![hanna]()

Kathleen Hanna. Photo courtesy of Leeta Harding. An IFC Films release.

If you could give a pocket definition of feminism to a young feminist today, what would it be?

It's about ending the oppression of all people. It's not just about women gaining power in the corporate boardroom or "leaning in" or whatever -- although I did find some value in that book. It's not about white women making it up the ladder to success. That's not what's it about. It's about ending the oppression of all people and ending all binaries. You know, the "this is what it means to be a woman and this is what it means to be a man." Or making these oppositions, that white people are the center of everything and minorities are the opposite, the adjunct or the margin.

And you have to challenge all that stuff at once. You can't do it all separately. You can't just talk about intersectionality, you need to actually, physically make it happen. I think that was the failure. We talked about it but we didn't make it happen.

Last question, since I know I'm pushing the schedule now. I ask a lot of people who their role models are, and a lot of the time, people answer this question with figures much older than them or long since dead -- with good reason of course. So, in your opinion, who are the young women or emerging figures that inspire you?

Grimes. Love her. I think she's great. The girl from Chvrches, whose name I can never remember, but I'm sure you know it...

Lauren Mayberry.

I think she's really inspirational. That [Guardian] article really inspired me -- to think of things in a different way.

"The Punk Singer" will be released by IFC Films in select movie theaters in New York City and Los Angeles on Friday, November 29. For more on Riot Grrrl, check out our articles on the Riot Grrrl Collection and "Alien She" exhibition.

![poster]()

But after more than a decade leading bands like Bikini Kill and Le Tigre, and speaking out against a media culture that continuously misunderstood third-wave feminism, Hanna stepped out of the spotlight. She was abruptly diagnosed with late-stage Lyme disease in the mid-2000s, a condition that left her battling a myriad of painful, nonspecific symptoms. So, with the riot grrrl phenomenon already splintered, Hanna left the music world to focus on her health.

Fast forward to 2013, and Hanna is, in a word, back. Back with a new band (The Julie Ruin), a new album and a new documentary based on her life. The film, titled "The Punk Singer," outlines the years before and after her departure from the stage, following her early years working in domestic violence shelters and strip clubs to her marriage to Beastie Boys singer Adam Horovitz to her struggles with Lyme disease treatments today.

We had the chance to chat with Hanna ahead of the premier of the documentary, directed by Sini Anderson and featuring the likes of Kim Gordon, Joan Jett, and Carrie Brownstein. Here's what the singer had to say about Pussy Riot, Fred Flintstone and the age of the internet.

One of the things that struck me about the documentary was the negative relationship you guys had with the media in the 1990s. [Bikini Kill led a media blackout in 1993 as a result of tense relations with news organizations.] Obviously, something has changed, otherwise I wouldn't have the chance to talk to you! So what's different?

Right. I think people are asking better questions. They're being more respectful. I'm seeing that a lot of young, feminist punk rockers have grown up and become journalists. Thank god! It's been pretty great. You know, every once in a while there's that sexist interviewer guy who wants to talk to me about my husband, and doesn't want to talk to me about my record. But today's been great.

Do you feel like that misunderstanding you experienced in the 1990s has disappeared for the most part?

Yeah. I also feel like I'm older, so if I get asked questions I don't want like, I can just pass on them. There was not buffer when I was in Bikini Kill. We didn't have a manager or a publicist. We often times didn't even have a roadie. So there was no buffer between us and the public, or us and fanzine writers. Because it wasn't just the mainstream press that was sexist. People found out I worked as a stripper and that's all they wanted to talk about. Or all they wanted to talk about was gender. We were a radical feminist band, and I was fine talking about gender, but I also wanted to talk about songs at some point. That really never happened. Then the riot grrrl thing was just, "Baby barrettes and sexy young girls. Their feminism is ridiculous. They've all been sexually abused and hate men." That was the media narrative. I think that's definitely changed and people have a real kind of respect now for what we did. I remember thinking history is going to be on our side. And I was right.

Now I give lectures and people listen to what I have to say and ask me great questions. They come up after and say that they feel really inspired. I'm not getting the shit anymore. They don't think, "You're a man-hating bitch." And members of my own community aren't mad that I'm getting more attention than other people. I'm older, so I'm also like, I fucking deserve the attention! I worked my ass off. I deserve to have a movie made about me. I deserve to write a record about whatever I want. You know what I mean? Why the fuck not?

You have quite the legacy. When I think about riot grrrl, one of the things I remember is Zine culture. And I think about how you almost did the internet before the internet was cool. You grasped the connective, DIY power of Tumblr and Twitter before any of these things existed. Does this thought ever cross your mind?

You know, for me, social media is really problematic. For somebody in a band, it's like this extra, unpaid job. To be perfectly honest, it's like you're expected to have an Instagram, Tumblr, everything. You're expected to be constantly giving people this information. The other day I was supposed to blog about how we were on the radio -- on WNYC -- and I was just so exhausted that I was just like, I can't get on the internet right now, I have other shit to do in real life. Sometimes I get really into it though; really into fucking around on my blog. And then sometimes I really just want to like... not check my email! [Laughs] You know what I mean? And not be doing all that.

But, when I think back to the '90s, I think we would totally have been all over that shit. We would have been tumbling and doing all this kind of stuff. A lot of people ask me the question, "Would riot grrrl exist in the internet age?" And, of course, I'm not sure. Because there's so much stuff on the internet. Everybody goes down a rabbit hole. I go on Facebook and then I click on something and I click on something and I click on something. I forget...

What you went online for in the first place?

Yeah! And I feel like the thing that was amazing about the '90s and the pre-internet era was that we wrote each other letters. We decorated them. We made each other packages. And it was really special when you got something from a friend. It was really special when you got a fan letter. One of my biggest regrets, actually, is that I had like three garbage bags of fan mail. It was my job in the band -- Tobi did some -- to answer our mail. Our mail was really intense. Really, really intense. I had people coming out to me personally as sexual abuse survivors, or saying, "I'm gay, and I've been kicked out of my family and social group." They were trusting me with this information when they didn't even trust their friends with it, or their parents. That, to me, was a huge part of the job. And I'm really sorry that I got rid of that stuff. But it was people's personal information and it's not the kind of thing you can put in an archive without asking each and every single person.

But yeah, three garbage bags. And I only started keeping them at a certain point. That just wouldn't happen now. Now it's emails. I think that when you have to sit down and write a letter to somebody you think about it more. You have more time, because you have to write it, put it in an envelope, address it, stamp it, go somewhere and mail it. I got a lot of amazing mail and I got a lot of hate mail. Today on the internet people can write whatever they want, though, about the Dum Dum Girls or whomever.

Or the Chvrches' singer, Lauren Mayberry [who wrote an op-ed for The Guardian titled "I Will Not Accept Online Misogyny"].

Right! Exactly. It's like anybody can go online and write this messed up shit and be totally anonymous. They aren't all these steps they have to take. I don't know if you ever watch "The Flintstones"?

[Laughs] Yeah, sure.

Ok, so you know when Fred Flintstone writes the evil letter to [his boss] Mr. Slate? When Fred Flintstone is pissed off and he goes and he puts it in the box, but then later he tries to get it out? It's like that. I feel like a lot of people would be Fred Flintstone trying to get the thing out. They'd be like, "That was stupid. I was just really pissed in that moment." You know what I mean? You had to really hate me then, to send me a package with a bunch of porn and hate mail in it.

Bikini Kill also had some pretty vocal critics who would show up at your shows and stand in front of you as you performed.

Yup.

So there is this strange difference between the confrontational critiques before the internet and this anonymous negativity that doesn't really have a face or anything tangible to attach to it. It also becomes very apparent, to people who aren't fans of the band that this negativity exists.

You know, I hadn't really heard of the band before the op-ed. I read the piece and that's what got me interested in the music. To me, it was this really positive thing. I was on a radio show in England and she was on it, and we talked about it. It was really great. I had said in an interview a really long time ago to just not read [hate mail]. Don't look for stuff. We already have enough hateful shit in our brain.

It's a thing thing with the internet -- and even pre-internet. There were a lot of people during riot grrrl that just really hated me. And it really hurt when it was other women. It's fine to have arguments and divisiveness within a movement. I think that's actually beneficial. But when there are people who are just shaming and blaming you, or using political rhetoric in an angry way just because they're pissed they want to be where you are. They want to be in a band or they want to be a leader, or whatever. Every kind of bad thing I had in my head I had said to me. I really had to get rid of that. Any negative thing you can think of about your body, or how you sing if you're a singer. You know, this one lyric was stupid. Someone's going to write that and reinforce that in your head. We shouldn't have to just deal with street harassment or these horrible comments on the internet. She's right. But the fact of the matter is, it's there. So I choose not to read it. I choose to ignore. Because my friends are not like that. And I get to hang out with people who don't say mean comments like that! [Laughs]

And then you fast forward. Pussy Riot. Did you envision that 15 years after Bikini Kill, women in Russia would be dressed in ski masks and neon clothing, using riot grrrl lyrics to combat authoritarianism in Russia?

No, absolutely not! I think it's the same way Ian MacKaye felt about straight edge. He was just writing shit in his own community for his friends. We were just doing it for our friends. We were inspired by people like G.B. Jones and homocore. Stuff that was coming out of Canada. Our friend Donna Dresch. People from San Francisco who were writing fanzines about being queer. That's what was inspiring us. And telling us that it's ok to write about what we were thinking about. And put it out in our scene.

And we were most worried about the guys in our scene. Because the first response we got was from these animal rights activists in our scene who wrote this really hateful fanzine that was all about this woman being raped and murdered and at the end you find out it's not a woman, it's a cat. And that was their response. That animal rights were more important. Trying to have a dialogue with those guys -- that's what we were thinking of. We weren't thinking, "This is the beginning of a movement. Then the Pussy Riot girls are going to get jailed and be challenging Putin." Like, totally not thinking of that. Of course not.

So when you look at the documentary after all the interviews and filming you went through, is there anything you think the film left out? Anything that you wish it would have covered from your life?

The thing that was left out... the thing that I talked about a lot and that I was really happy that I talked about was kind of what I saw as the failures of riot grrrl. And the stuff that I'm telling you now. That there was hatred towards me and my band that wasn't just from angry men. There was this whole faction of people who were mad at me because I was the wrong kind of feminist. There was a lot of stuff about race and class that was left out of the discussion or was discussed in a completely different way or inappropriate way in factions of Riot Grrrl. And I talked about that during filming and finally felt safe talking about it. But the good news is, there's a movie being made about Riot Grrl too, and I said all those things in that too.

If you could give a pocket definition of feminism to a young feminist today, what would it be?

It's about ending the oppression of all people. It's not just about women gaining power in the corporate boardroom or "leaning in" or whatever -- although I did find some value in that book. It's not about white women making it up the ladder to success. That's not what's it about. It's about ending the oppression of all people and ending all binaries. You know, the "this is what it means to be a woman and this is what it means to be a man." Or making these oppositions, that white people are the center of everything and minorities are the opposite, the adjunct or the margin.

And you have to challenge all that stuff at once. You can't do it all separately. You can't just talk about intersectionality, you need to actually, physically make it happen. I think that was the failure. We talked about it but we didn't make it happen.

Last question, since I know I'm pushing the schedule now. I ask a lot of people who their role models are, and a lot of the time, people answer this question with figures much older than them or long since dead -- with good reason of course. So, in your opinion, who are the young women or emerging figures that inspire you?

Grimes. Love her. I think she's great. The girl from Chvrches, whose name I can never remember, but I'm sure you know it...

Lauren Mayberry.

I think she's really inspirational. That [Guardian] article really inspired me -- to think of things in a different way.

"The Punk Singer" will be released by IFC Films in select movie theaters in New York City and Los Angeles on Friday, November 29. For more on Riot Grrrl, check out our articles on the Riot Grrrl Collection and "Alien She" exhibition.