Louis Bourgeois is a feminist art icon, even if she -- in some mythical afterlife populated by giant spiders and contorted, alien figures -- would hate the label. When she was alive, she was aloof on the subject. "Some of my works are, or try to be feminist, and others are not feminist," she proclaimed in an interview with the San Francisco Museum of Art.

"I am lucky to have been brought up by a mother who was a feminist and fortunate enough to have married a husband who was a feminist, and I have raised sons who are feminists," Germaine Greer quoted her as saying in The Guardian, not long after Bourgeois' death in 2010. The artist, famous for her mammoth sculptures of spiders, pointedly leaves herself out of the list, insinuating not a rejection of the -ism, necessarily, but perhaps a bit of condescension toward critics eager to associate her with the term, no matter her opinions.

![lb]()

Louise Bourgeois, Spider, 2003. Collection The Easton Foundation. Photo: Christopher Burke.

Bourgeois does owe a lot to the feminist movement. Born in Paris in 1911, she spent many of her early years known merely as the wife of Robert Goldwater, the American art historian with whom she moved to New York in the late 1930s. Though she drew, painted, sculpted and printed throughout the 1940s and '50s, Bourgeois didn't receive real art world attention until her 50s. She had to wait more than a few years before she moved from the periphery of art critics' minds to somewhere closer to the center. During that time, the feminist movement was blooming.

"The specific agent of change was feminism, the most pervasive and radical of the many 'pluralist' constituencies of the last ten years," Robert Storr wrote in Art in America back in 1983, around 8 years after she graced the cover of Artforum and one year after her retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art. "And more particularly the insistence of feminist artists and critics we look hard at for whatever was formerly considered 'marginal' in art, and hardest of all at the very notion that a 'mainstream' existed."

For a woman who loathed the term "woman artist," it seems to many so important that she was a woman artist at the time she rose to recognition. Amidst the hyper masculine aesthetic of the Abstract Expressionists and the coy fraternity of Surrealism, she quite literally forged ahead, casting "anti-form" creatures from marble and bronze. From her "Femme Maison (Woman House)" paintings created circa 1946-47, in which the bodies of nude women are forcefully squished into the confining spaces of a home, to her 1968 sculpture, "Janus Fleuri," a piece curiously sexualized if not for its inclusion of imagery that resembles both male and female genitalia, themes of femininity and gender roles reared their heads.

![chair]()

Louise Bourgeois, Lady in Waiting, 2003. Collection The Easton Foundation. Photo: Christopher Burke.

A fascination with the body is apparent throughout her career. While men like Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman were swimming in color fields, she rendered her self-portrait as a torso, pieced together with bizarre bulges and crevices that seem endlessly out of place. "That, she said, was how she felt about her physical self," Michael McNay wrote, "and by extension, how women generally felt, even while they studied copies of Vogue or Harper's Bazaar."

The list could go on: There's the 1968 piece, "Fillette," which was obviously a massive penis sculpture, one that happened to make its way into a photograph by Robert Mapplethorpe. There's the 1974 tableau, "The Destruction of the Father," a gathering of mammary-like objects and penile knobs said to represent the "sacrificial evisceration of a body," more specifically "a pompous father, whose presence deadens the dinner hour night after night." There's the 1984 "Nature Study," appearing like a headless sphinx covered in breasts and equipped with Doberman Pinscher-esque claws.

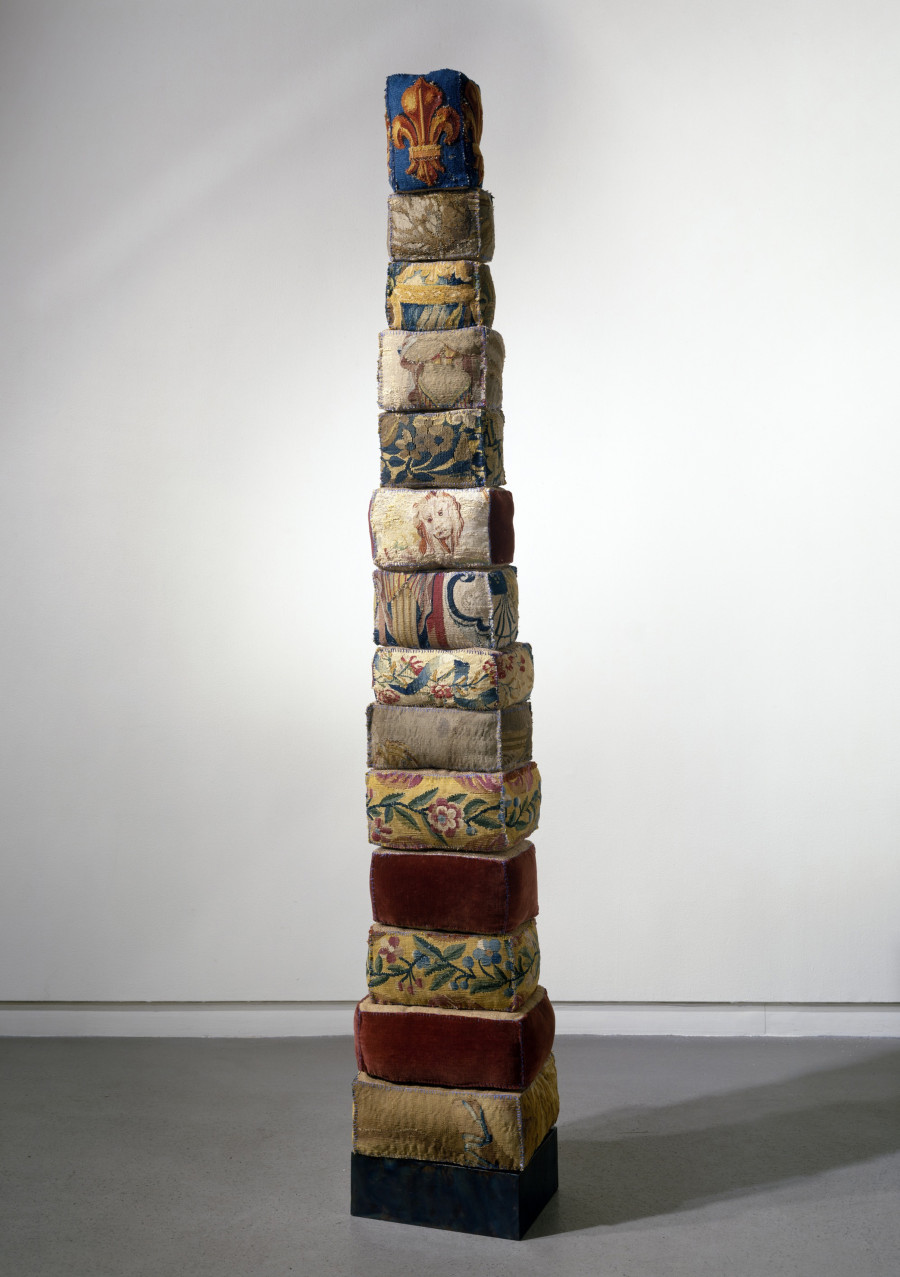

![stacks]()

Louise Bourgeois, Untitled, 2000. Private Collection, Courtesy Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Christopher Burke.

She might not have been singing the song of feminist sirens, but her work relentlessly juxtaposed male and female forms, revealing hybrid bodies and aggressive amalgamations of phallic and yonic imagery; sexual subject matter from a woman's gaze.

Her vocalized stance on a woman's social position versus that of a man's was at times confusing. She seemed simultaneously angry at the idea that masculinity and its own brand of ego were wrapped up in a penis, and disappointed that feminine beauty often went hand-in-hand with passivity.

"It's a dialogue between a man and a woman," Bourgeois recounted in another interview with SFMOMA, cryptically titled "Louis Bourgeois on Gender Roles." She outlines an interesting, if not depressing scenario attached to a phantom piece of art, a retelling that's almost incomprehensible as a total story, but a strange exchange nonetheless that gives glimpses of her own sentiments toward men and women.

![face]()

Louise Bourgeois, Untitled, 2002. Collection The Easton Foundation. Photo: Christopher Burke.

"You know what men are like," she says to an unidentified male companion. "For example, it's about a man who discovers a vaccine. He discovers a vaccine, he's a bigwig. As for her, she stumbles upon a little sofa at the auction rooms. Understand? That's the relationship. If that doesn't convince you, I can give you other examples. For example, when he speaks. Of course, when he speaks the world stops in its tracks. Whereas she, she just chitchats. And when it's time for dinner, he's the chef. He prepares this wonderful meal! Whereas she, she just cooks. Just cooks. And he feels good, he whistles. He whistles like a blackbird. Whereas she whistles to herself. And when he feels good he touches you, right? He touches you. Whereas she, she brushes against you. To no effect... like pissing in the wind."

It wasn't until the 1990s that she went the way of the spider. Sculpting for heights of 35 feet, she created her first arachnid in 1999 and they quickly proliferated, as spiders are wont to do. Titled "Maman," the spindly creatures and their egg sacs, made from stainless steal, marble and bronze, stood as tributes to Bourgeois' mother, Josephine. "The Spider is an ode to my mother. She was my best friend. Like a spider, my mother was a weaver... spiders are helpful and protective, just like my mother."

![stack2]()

Louise Bourgeois, Untitled, 2001. Collection The Easton Foundation. Photo: Christopher Burke.

Dark, ominous, and absent of the smooth curves of femininity, "Maman" projected a very different female object in places like Bilbao, Tokyo and Ottawa. Frightening yet maternal, sinister yet life-giving, antagonistic yet martyred -- these contradictions seemed Bourgeois' way of breaking through the gender binary, up until her last days at the age of 98. "I have fantastic pleasure in breaking everything," she once said. Yet towards the end of her life, she created, with delicacy, particularly in the realm of tapestry. This was yet another way of honoring her mother, and achieved a sense of "reparation."

![spider]()

Louise Bourgeois, Spider, 2007. Collection The Easton Foundation. Photo: Frédéric Delpech.

Her defiance, her arguably unmatched persistence, her visual tenacity -- these qualities will forever cement Bourgeois' place in feminist art history. Not because she's a woman artist -- a label hardly derogatory -- but because she pushed the boundaries of what it meant to make art.

“Feminist art is not some tiny creek running off the great river of real art," as Andrea Dworkin declared. "It is not some crack in an otherwise flawless stone. It is, quite spectacularly I think, art which is not based on the subjugation of one half of the species." Bourgeois should be proud to count herself amongst those who made feminist art.

"Louise Bourgeois L’araignée et les tapisseries" is currently on view at Hauser & Wirth Zürich until July 26. All images included in this post are courtesy of Hauser & Wirth unless otherwise noted.

"I am lucky to have been brought up by a mother who was a feminist and fortunate enough to have married a husband who was a feminist, and I have raised sons who are feminists," Germaine Greer quoted her as saying in The Guardian, not long after Bourgeois' death in 2010. The artist, famous for her mammoth sculptures of spiders, pointedly leaves herself out of the list, insinuating not a rejection of the -ism, necessarily, but perhaps a bit of condescension toward critics eager to associate her with the term, no matter her opinions.

Bourgeois does owe a lot to the feminist movement. Born in Paris in 1911, she spent many of her early years known merely as the wife of Robert Goldwater, the American art historian with whom she moved to New York in the late 1930s. Though she drew, painted, sculpted and printed throughout the 1940s and '50s, Bourgeois didn't receive real art world attention until her 50s. She had to wait more than a few years before she moved from the periphery of art critics' minds to somewhere closer to the center. During that time, the feminist movement was blooming.

"The specific agent of change was feminism, the most pervasive and radical of the many 'pluralist' constituencies of the last ten years," Robert Storr wrote in Art in America back in 1983, around 8 years after she graced the cover of Artforum and one year after her retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art. "And more particularly the insistence of feminist artists and critics we look hard at for whatever was formerly considered 'marginal' in art, and hardest of all at the very notion that a 'mainstream' existed."

For a woman who loathed the term "woman artist," it seems to many so important that she was a woman artist at the time she rose to recognition. Amidst the hyper masculine aesthetic of the Abstract Expressionists and the coy fraternity of Surrealism, she quite literally forged ahead, casting "anti-form" creatures from marble and bronze. From her "Femme Maison (Woman House)" paintings created circa 1946-47, in which the bodies of nude women are forcefully squished into the confining spaces of a home, to her 1968 sculpture, "Janus Fleuri," a piece curiously sexualized if not for its inclusion of imagery that resembles both male and female genitalia, themes of femininity and gender roles reared their heads.

A fascination with the body is apparent throughout her career. While men like Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman were swimming in color fields, she rendered her self-portrait as a torso, pieced together with bizarre bulges and crevices that seem endlessly out of place. "That, she said, was how she felt about her physical self," Michael McNay wrote, "and by extension, how women generally felt, even while they studied copies of Vogue or Harper's Bazaar."

The list could go on: There's the 1968 piece, "Fillette," which was obviously a massive penis sculpture, one that happened to make its way into a photograph by Robert Mapplethorpe. There's the 1974 tableau, "The Destruction of the Father," a gathering of mammary-like objects and penile knobs said to represent the "sacrificial evisceration of a body," more specifically "a pompous father, whose presence deadens the dinner hour night after night." There's the 1984 "Nature Study," appearing like a headless sphinx covered in breasts and equipped with Doberman Pinscher-esque claws.

She might not have been singing the song of feminist sirens, but her work relentlessly juxtaposed male and female forms, revealing hybrid bodies and aggressive amalgamations of phallic and yonic imagery; sexual subject matter from a woman's gaze.

Her vocalized stance on a woman's social position versus that of a man's was at times confusing. She seemed simultaneously angry at the idea that masculinity and its own brand of ego were wrapped up in a penis, and disappointed that feminine beauty often went hand-in-hand with passivity.

"It's a dialogue between a man and a woman," Bourgeois recounted in another interview with SFMOMA, cryptically titled "Louis Bourgeois on Gender Roles." She outlines an interesting, if not depressing scenario attached to a phantom piece of art, a retelling that's almost incomprehensible as a total story, but a strange exchange nonetheless that gives glimpses of her own sentiments toward men and women.

"You know what men are like," she says to an unidentified male companion. "For example, it's about a man who discovers a vaccine. He discovers a vaccine, he's a bigwig. As for her, she stumbles upon a little sofa at the auction rooms. Understand? That's the relationship. If that doesn't convince you, I can give you other examples. For example, when he speaks. Of course, when he speaks the world stops in its tracks. Whereas she, she just chitchats. And when it's time for dinner, he's the chef. He prepares this wonderful meal! Whereas she, she just cooks. Just cooks. And he feels good, he whistles. He whistles like a blackbird. Whereas she whistles to herself. And when he feels good he touches you, right? He touches you. Whereas she, she brushes against you. To no effect... like pissing in the wind."

It wasn't until the 1990s that she went the way of the spider. Sculpting for heights of 35 feet, she created her first arachnid in 1999 and they quickly proliferated, as spiders are wont to do. Titled "Maman," the spindly creatures and their egg sacs, made from stainless steal, marble and bronze, stood as tributes to Bourgeois' mother, Josephine. "The Spider is an ode to my mother. She was my best friend. Like a spider, my mother was a weaver... spiders are helpful and protective, just like my mother."

Dark, ominous, and absent of the smooth curves of femininity, "Maman" projected a very different female object in places like Bilbao, Tokyo and Ottawa. Frightening yet maternal, sinister yet life-giving, antagonistic yet martyred -- these contradictions seemed Bourgeois' way of breaking through the gender binary, up until her last days at the age of 98. "I have fantastic pleasure in breaking everything," she once said. Yet towards the end of her life, she created, with delicacy, particularly in the realm of tapestry. This was yet another way of honoring her mother, and achieved a sense of "reparation."

Her defiance, her arguably unmatched persistence, her visual tenacity -- these qualities will forever cement Bourgeois' place in feminist art history. Not because she's a woman artist -- a label hardly derogatory -- but because she pushed the boundaries of what it meant to make art.

“Feminist art is not some tiny creek running off the great river of real art," as Andrea Dworkin declared. "It is not some crack in an otherwise flawless stone. It is, quite spectacularly I think, art which is not based on the subjugation of one half of the species." Bourgeois should be proud to count herself amongst those who made feminist art.

"Louise Bourgeois L’araignée et les tapisseries" is currently on view at Hauser & Wirth Zürich until July 26. All images included in this post are courtesy of Hauser & Wirth unless otherwise noted.