Over fifty five contemporary artists have gathered in St. Petersburg to infiltrate one of the world's oldest museums. Why? Because Manifesta, the nomadic European Biennial that sets up shop in a different city every two years to bridge the gap between East and West, fixed its sights on Russia for the 10th version of the festival.

![lada]()

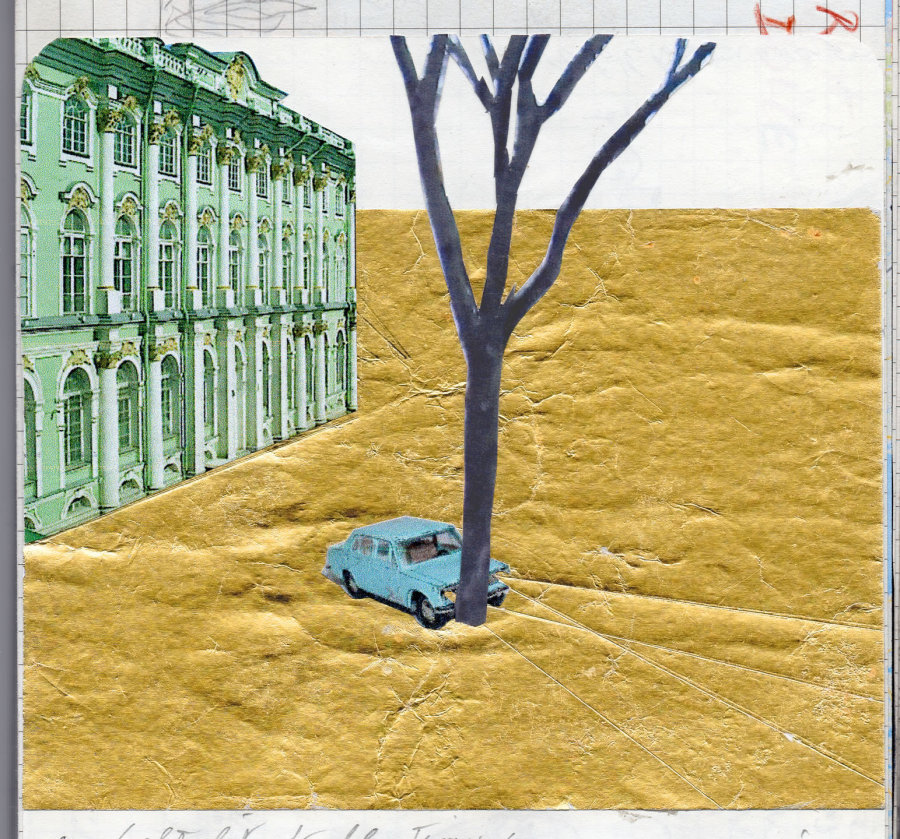

Francis Alÿs, Draft for Lada Kopeika Project, 2014, Collage with gold leaf, 11.5 x 13 cm, courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner Gallery.

The timing couldn't have been worse. As curators began planning Manifesta 10, tensions between Ukraine -- a country undergoing yet another revolution -- and Russia intensified. Russian forces eventually flooded into Crimea, a disputed peninsula on the Black Sea between the two countries, and the world observed territorial annexation in the 21st century. While the diplomatic image of the former Soviet Union dipped below satisfactory, Russia's domestic affairs fared no better. Anti-gay legislation and state-led censorship peaked. Authoritarianism seemed all but on the rise for a nation spanning over one-eighth of planet Earth.

Despite the obvious obstacles, the Manifesta team forged forward. While some artists pulled their support of the biennial by boycotting, the festival remained steadfast. Manifesta curator Kasper König, along with State Hermitage Museum director M. Piotrovsky and Manifesta director Hedwig Fijen, made their intentions clear early on.

"Manifesta stands for artistic independence and has a responsibility to art and artists and those who wish to engage with the context in which we situate ourselves," Fijen stated in a press release last March. "Our work is one of debate, negotiation, mediation, and diplomacy, that does not shy away from the conflicts of our time. At a time when everything tends to be read through a geo-political lens, art is there to provide complexity and nuance.”

![dumas]()

Marlene Dumas, Alan Turing, 2014. Ink on paper, 44 x 35 cm.Photo credit: Bernard Ruijgrok Piezographics. Copyright and courtesy: Marlene Dumas. Commissioned by Manifesta 10 Saint Petersburg, Russia.

Before the biennial officially opened on June 28, König and his team faced unfulfilled financial agreements with the city of St. Petersburg and a slew of other local bureaucratic setbacks that forced staff to go unpaid for two months. Now, more than two weeks into the biennial, Manifesta has left only some of the hurdles behind it. The show has, as they say, gone on anyway, and critical responses have been mixed thus far.

"A few terrific works don't make a great or telling exhibition," Adrian Searle wrote in The Guardian. "It all feels too wary. It offers too little conflict and not enough hope."

"There’s a refreshingly solid balance between male and female artists in the show," Alexander Forbes proclaimed in Artnet, describing the show as "a sort of anti-teleological view on artistic developments, both in aesthetics and society at large, since the fall of the Berlin Wall."

Like most art fairs of this scale, reviews will fluctuate, with some taking a shining to the way exhibitors and curators have framed 25 years of post-USSR art making, and others not. As far as the biennial's ability to raise questions in and around the art world, there's no denying the festival's power. From Marlene Dumas to Gerhard Richter, Nicole Eisenman to Wolfgang Tillmans, the participating artists confront violence and sexuality in ways that only shine a spotlight on the deficiencies of present day Eastern Europe -- even if those deficiencies have wound their way into Manifesta's temporary home.

Check out a preview of Manifesta 10, on view until October 31 in St. Petersburg's State Hermitage Museum, above and let us know your thoughts on the event in the comments.

The timing couldn't have been worse. As curators began planning Manifesta 10, tensions between Ukraine -- a country undergoing yet another revolution -- and Russia intensified. Russian forces eventually flooded into Crimea, a disputed peninsula on the Black Sea between the two countries, and the world observed territorial annexation in the 21st century. While the diplomatic image of the former Soviet Union dipped below satisfactory, Russia's domestic affairs fared no better. Anti-gay legislation and state-led censorship peaked. Authoritarianism seemed all but on the rise for a nation spanning over one-eighth of planet Earth.

Despite the obvious obstacles, the Manifesta team forged forward. While some artists pulled their support of the biennial by boycotting, the festival remained steadfast. Manifesta curator Kasper König, along with State Hermitage Museum director M. Piotrovsky and Manifesta director Hedwig Fijen, made their intentions clear early on.

"Manifesta stands for artistic independence and has a responsibility to art and artists and those who wish to engage with the context in which we situate ourselves," Fijen stated in a press release last March. "Our work is one of debate, negotiation, mediation, and diplomacy, that does not shy away from the conflicts of our time. At a time when everything tends to be read through a geo-political lens, art is there to provide complexity and nuance.”

Before the biennial officially opened on June 28, König and his team faced unfulfilled financial agreements with the city of St. Petersburg and a slew of other local bureaucratic setbacks that forced staff to go unpaid for two months. Now, more than two weeks into the biennial, Manifesta has left only some of the hurdles behind it. The show has, as they say, gone on anyway, and critical responses have been mixed thus far.

"A few terrific works don't make a great or telling exhibition," Adrian Searle wrote in The Guardian. "It all feels too wary. It offers too little conflict and not enough hope."

"There’s a refreshingly solid balance between male and female artists in the show," Alexander Forbes proclaimed in Artnet, describing the show as "a sort of anti-teleological view on artistic developments, both in aesthetics and society at large, since the fall of the Berlin Wall."

Like most art fairs of this scale, reviews will fluctuate, with some taking a shining to the way exhibitors and curators have framed 25 years of post-USSR art making, and others not. As far as the biennial's ability to raise questions in and around the art world, there's no denying the festival's power. From Marlene Dumas to Gerhard Richter, Nicole Eisenman to Wolfgang Tillmans, the participating artists confront violence and sexuality in ways that only shine a spotlight on the deficiencies of present day Eastern Europe -- even if those deficiencies have wound their way into Manifesta's temporary home.

Check out a preview of Manifesta 10, on view until October 31 in St. Petersburg's State Hermitage Museum, above and let us know your thoughts on the event in the comments.