The 1980s were a tumultuous and crucial time for the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) community, particularly in midst of the HIV/AIDS crisis and the lack of understanding surrounding the ways this disease was being contracted and affecting our bodies.

Photographer Thomas Alleman moved to San Francisco in 1985 and began documenting his community and experiences for The San Francisco Sentinel, a queer weekly tabloid modeled after The Village Voice. The result was this stunning collection of photos that highlights a huge spectrum of queer identity thriving during this time period.

This collection of photos debuted at the Jewett Gallery in San Francisco in December 2012 under the title "Dancing in the Dragon’s Jaws." Recently, The Huffington Post chatted with the photographer about his work and his time in San Francisco at the height of the AIDS crisis.

![gay]()

The Huffington Post: Who are the individuals documented in these photos?

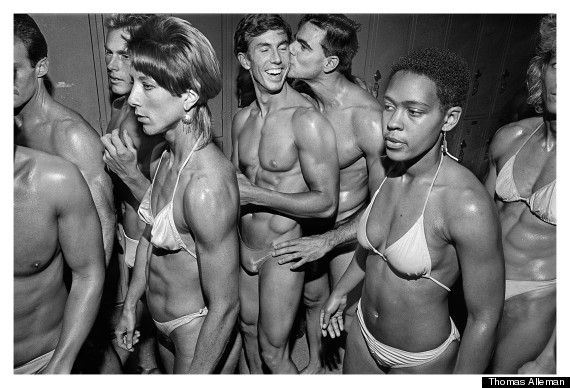

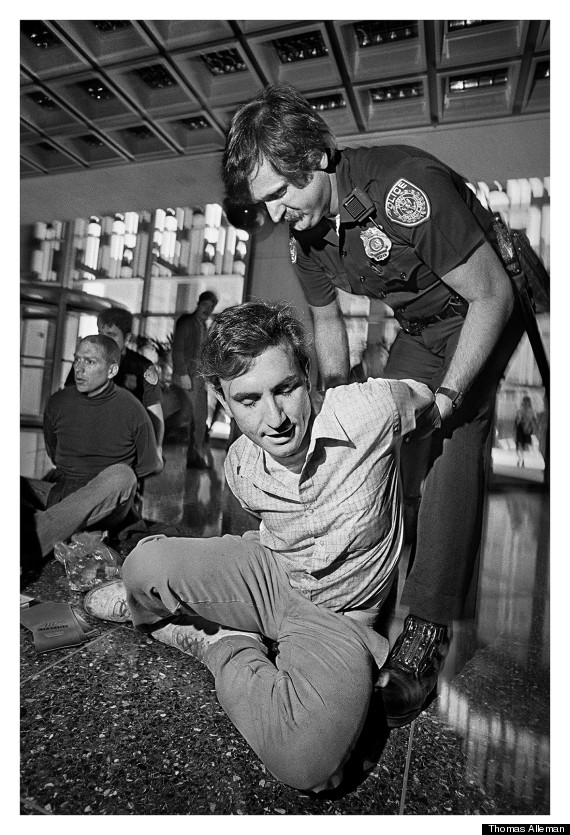

Thomas Alleman: I made these pictures while working with a very sassy, very queer weekly tabloid in San Francisco’s gay community, The Sentinel. Quite consciously, it was modeled after The Village Voice, in New York -- the insurgent design, the trenchant political style, the smartypants irony -- and I, as luck would have it, had studied raptly the work of the Voice’s avant photojournalists, Sylvia Plachy and James Hamilton, while I was developing my own technique back in Michigan. I was working in a style, in those days, that had been developed by cutting-edge documentary photographers on the East Coast and in Europe in the seventies, but which hadn’t quite made it to California, except in some punk communities. We used wide lenses, which forced us very close to the action, and hand-held flashes, which created a blitz of invasive white light; often, our angles were crazy and our horizons askew, as if we were banging and stumbling through a bar fight. It was all very aggressive, very “in your face,” very ironic. But I had the weird feeling that one could use those methods in the service of a more nuanced, more “tender” document, and that’s what I tried to do on Castro Street in the years I worked there.

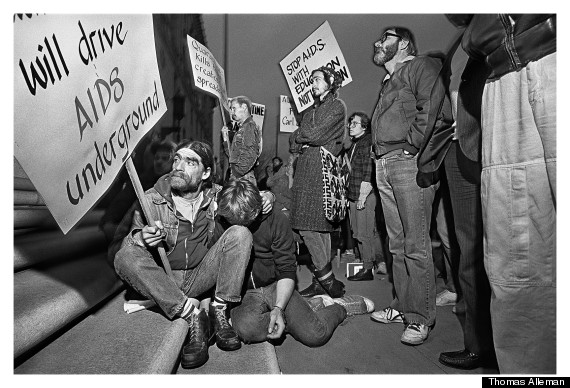

But that style wasn’t often used to make intimate pictures of private life. Certainly, Nan Goldin and Mary Ellen Mark excelled at that, but at that time most of those pictures were done in public, as Garry Winogrand and Bruce Davidson had demonstrated. So, my own work witnesses the self-selected group of gay San Franciscans who chose to participate in the public life of the Castro, whether in drag bars or at demonstrations and street parties, or in attendance at candlelight vigils that remembered those whom AIDS had taken so quickly. The folks who stayed in their apartments, or were sequestered at Ward 5B at San Francisco General Hospital, were outside the purview of my strobe light, and both my editors and I agreed that that was the only humane stance to take: the “straight press” was pursuing stark documentary images of individual carnage, but we knew that our readers were already too-aware of bedside vigils and funeral arrangements; they didn’t need their “hometown” weekly to recapitulate that dreary, daily horror.

![gay]()

For a historical reference point for these photos, what was happening in San Francisco during this moment in time?

The Castro had been an incredibly vital place in the 1970's, perhaps as Harlem had been during its famous "Renaissance" in the '20s. A group of people who for countless years had been marginalized, cast-out, despised, came together to live in a neighborhood where they built their own very vibrant culture. Because of San Francisco's legendary openness and "tolerance" -- which was often real, and sometimes an illusion -- they were kinda-pretty-much left to live in peace; because of their advantages in education and numbers, and driven by ambition and anger, they carved out a political presence that couldn't be ignored, and which furthered their security and allowed the culture to flower even more fearlessly.

People who'd lived through those years -- and folks who moved to the Castro in droves to join the party -- didn't forget the joy and promise of all that, even after the tsunami wave of HIV and AIDS crashed onto the neighborhood in the early '80s. They were still the same beautiful, brilliant, lovers-of-life that they'd always been. But many of them died, and others were heartbroken and horrified and outraged, and that does take a toll on the spirit of any tribe. Still, that "liveliness" -- that passion -- was so essential, so much a part of the community, that it just couldn't be extinguished by something as dispassionate as a plague. So, while many of the pictures in this portfolio demonstrate a community in lamentation, many others are about indignation and resolve, and most are about love and life. And disco and drag.

![gay]()

Why do you think these images are important?

I’m happy to report that I’ve heard the same thing again and again from reviewers, curators and editors: the photographs of “Dancing In the Dragon’s Jaws” have a thematic coherence as a group of historical, visual documents, and that gives the whole portfolio a unity, an integrity and a life of it’s own that those can appeal to viewers for many years to come.

Whatever might’ve felt clinical or invasive about the frontal, very democratic wash of light from my strobe -- whatever might’ve seemed overwhelming and anarchic in the wealth of indiscriminate detail those wide lenses captured -- all of that seems now to be a boon to our sense of historic time and place in the pictures: in balance with the subtext of fear and anger and doom that prevails underneath these images is a vivid record of faces and hands, hairstyles and clothes and the local topography of that neighborhood. That’s not to be taken lightly, I think: those splendid folks lived in a real, tangible world of objects and bodies, and we misunderstand them a bit if we only remember their disease or their legend, if our recollection is abstracted by simple notions of “loss” or “old” or “gone."

It’s not trivial, for example, to notice that, in all those pictures of demonstrations and vigils, not a single participant is wearing a shirt, sweater, jacket or hat that features corporate branding (except one guy, in a Giants jersey). That obvious fact communicates a great deal about the world that plague arrived into: the last era of un-wired, unmediated, unmanaged public intercourse, before everything became a marketing exercise for branded products, when people formed connections with their neighbors based less on consumption and more on immediate proximity and affinity. The myriad physical details of that affinity, that proximity -- the marchers, arm in arm, and the revelers in the ballroom -- are of great value to us today: now that much (though, not all) of the most urgent struggle is over, we can now discern the fighters from the fight, the dancers from the dance, and look at them with strobe-lit, wide-angle wonder, esteem and amazement.

Check out a selection of images from "Dancing In The Dragon's Jaws" below and head here for more information on Alleman.

Photographer Thomas Alleman moved to San Francisco in 1985 and began documenting his community and experiences for The San Francisco Sentinel, a queer weekly tabloid modeled after The Village Voice. The result was this stunning collection of photos that highlights a huge spectrum of queer identity thriving during this time period.

This collection of photos debuted at the Jewett Gallery in San Francisco in December 2012 under the title "Dancing in the Dragon’s Jaws." Recently, The Huffington Post chatted with the photographer about his work and his time in San Francisco at the height of the AIDS crisis.

The Huffington Post: Who are the individuals documented in these photos?

Thomas Alleman: I made these pictures while working with a very sassy, very queer weekly tabloid in San Francisco’s gay community, The Sentinel. Quite consciously, it was modeled after The Village Voice, in New York -- the insurgent design, the trenchant political style, the smartypants irony -- and I, as luck would have it, had studied raptly the work of the Voice’s avant photojournalists, Sylvia Plachy and James Hamilton, while I was developing my own technique back in Michigan. I was working in a style, in those days, that had been developed by cutting-edge documentary photographers on the East Coast and in Europe in the seventies, but which hadn’t quite made it to California, except in some punk communities. We used wide lenses, which forced us very close to the action, and hand-held flashes, which created a blitz of invasive white light; often, our angles were crazy and our horizons askew, as if we were banging and stumbling through a bar fight. It was all very aggressive, very “in your face,” very ironic. But I had the weird feeling that one could use those methods in the service of a more nuanced, more “tender” document, and that’s what I tried to do on Castro Street in the years I worked there.

But that style wasn’t often used to make intimate pictures of private life. Certainly, Nan Goldin and Mary Ellen Mark excelled at that, but at that time most of those pictures were done in public, as Garry Winogrand and Bruce Davidson had demonstrated. So, my own work witnesses the self-selected group of gay San Franciscans who chose to participate in the public life of the Castro, whether in drag bars or at demonstrations and street parties, or in attendance at candlelight vigils that remembered those whom AIDS had taken so quickly. The folks who stayed in their apartments, or were sequestered at Ward 5B at San Francisco General Hospital, were outside the purview of my strobe light, and both my editors and I agreed that that was the only humane stance to take: the “straight press” was pursuing stark documentary images of individual carnage, but we knew that our readers were already too-aware of bedside vigils and funeral arrangements; they didn’t need their “hometown” weekly to recapitulate that dreary, daily horror.

For a historical reference point for these photos, what was happening in San Francisco during this moment in time?

The Castro had been an incredibly vital place in the 1970's, perhaps as Harlem had been during its famous "Renaissance" in the '20s. A group of people who for countless years had been marginalized, cast-out, despised, came together to live in a neighborhood where they built their own very vibrant culture. Because of San Francisco's legendary openness and "tolerance" -- which was often real, and sometimes an illusion -- they were kinda-pretty-much left to live in peace; because of their advantages in education and numbers, and driven by ambition and anger, they carved out a political presence that couldn't be ignored, and which furthered their security and allowed the culture to flower even more fearlessly.

People who'd lived through those years -- and folks who moved to the Castro in droves to join the party -- didn't forget the joy and promise of all that, even after the tsunami wave of HIV and AIDS crashed onto the neighborhood in the early '80s. They were still the same beautiful, brilliant, lovers-of-life that they'd always been. But many of them died, and others were heartbroken and horrified and outraged, and that does take a toll on the spirit of any tribe. Still, that "liveliness" -- that passion -- was so essential, so much a part of the community, that it just couldn't be extinguished by something as dispassionate as a plague. So, while many of the pictures in this portfolio demonstrate a community in lamentation, many others are about indignation and resolve, and most are about love and life. And disco and drag.

Why do you think these images are important?

I’m happy to report that I’ve heard the same thing again and again from reviewers, curators and editors: the photographs of “Dancing In the Dragon’s Jaws” have a thematic coherence as a group of historical, visual documents, and that gives the whole portfolio a unity, an integrity and a life of it’s own that those can appeal to viewers for many years to come.

Whatever might’ve felt clinical or invasive about the frontal, very democratic wash of light from my strobe -- whatever might’ve seemed overwhelming and anarchic in the wealth of indiscriminate detail those wide lenses captured -- all of that seems now to be a boon to our sense of historic time and place in the pictures: in balance with the subtext of fear and anger and doom that prevails underneath these images is a vivid record of faces and hands, hairstyles and clothes and the local topography of that neighborhood. That’s not to be taken lightly, I think: those splendid folks lived in a real, tangible world of objects and bodies, and we misunderstand them a bit if we only remember their disease or their legend, if our recollection is abstracted by simple notions of “loss” or “old” or “gone."

It’s not trivial, for example, to notice that, in all those pictures of demonstrations and vigils, not a single participant is wearing a shirt, sweater, jacket or hat that features corporate branding (except one guy, in a Giants jersey). That obvious fact communicates a great deal about the world that plague arrived into: the last era of un-wired, unmediated, unmanaged public intercourse, before everything became a marketing exercise for branded products, when people formed connections with their neighbors based less on consumption and more on immediate proximity and affinity. The myriad physical details of that affinity, that proximity -- the marchers, arm in arm, and the revelers in the ballroom -- are of great value to us today: now that much (though, not all) of the most urgent struggle is over, we can now discern the fighters from the fight, the dancers from the dance, and look at them with strobe-lit, wide-angle wonder, esteem and amazement.

Check out a selection of images from "Dancing In The Dragon's Jaws" below and head here for more information on Alleman.