If people are predicted to die constructing a building you designed, what would you do?

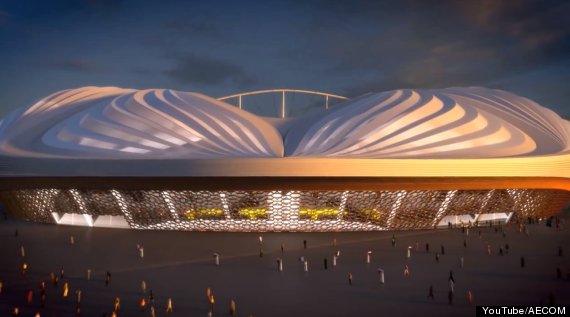

This is the question facing architect Zaha Hadid, whose Al Wakrah is the most famous of the stadiums rising out of the desert for the 2022 World Cup. Its fame isn’t for the high-profile matches it will host, nor for its size (Al Wakrah is neither the largest nor most critical of the dozen sites for the Qatar games), but for its shape. Though the stadium is meant to reference a traditional Arabic fishing boat, when the designs were revealed last year, everyone from Jon Stewart to the feminist site Jezebel had a chuckle over how much it looks like a vulva.

![aecom]()

The notoriety of the design may be why Hadid -- and not, say, Norman Foster or Albert Speer Jr., starchitects who also won World Cup bids -- is enmeshed in a far more serious scandal: a rash of deaths in the name of the tournament.

Hadid -- an Iraqi-born British icon and the first woman to win the famed Pritzker Prize -- is also arguably the best known architect of the bunch. Her stadium is also scheduled to be completed first. While reports indicate that advance construction on her site began in January, it is not known whether any workers have died at Al Wakrah specifically.

Hadid's office did not respond to several requests for comment this week on the World Cup-worker deaths.

According to a recent investigation by The Guardian, since 2012, nearly 900 immigrant workers from India and Nepal have died from circumstances largely related to 2022 World Cup labor. If present conditions persist, up to 4,000 more may die “before a ball is kicked in 2022,” according to the International Trade Union Confederation, which monitors workers’ rights across the globe.

As of last fall, more than half of the dead had succumbed to workplace accidents or heart attacks triggered by the heat of the desert, coupled with squalid living quarters that often drive laborers to sleep on their roofs. One laborer told The Guardian he was physically assaulted by his employer after being forced to work for more than 36 hours on no food.

This in a country so oil rich it’s spending $200 billion on a sports event. That’s $100,00 per capita, versus the $350 per capita lavished on the pricey Sochi Olympic Games, $73 per capita estimated for Brazil’s World Cup, and $54 per capita spent by South Africa when it hosted the tournament (not counting Qatar’s likely hidden costs, in the form of alleged bribes to win the bid in the first place.)

“The overall picture is of one of the richest nations exploiting one of the poorest to get ready for the world's most popular sporting tournament,” The Guardian report concludes.

How does Hadid fit into this mess? By claiming she doesn’t.

The architect drew outrage and criticism last week when she told The Guardian that she has “nothing to do with the workers.”

“I think that's an issue the government –- if there's a problem –- should pick up,” she added. “Hopefully, these things will be resolved … It's not my duty as an architect to look at it … I have no power to do anything about it."

She wasn’t helped by that qualifier -- “if there’s a problem” -- the casualness of which hardly relayed caution or concern. Hundreds of deaths is certainly a problem. The backlash has been widespread, and the headlines rough: “Zaha Hadid Is An Awful Human Being,” starts one, on the art world news site Hyperallergic.

But is Hadid correct?

According to architect Phillip H. Gerou, yes, technically speaking. Gerou, a past member of the ethics board for the American Institute of Architects, told The Huffington Post that architectural ethics codes typically ascribe the “duty” of caring for worker safety to the contractor.

“The contractor necessarily needs to keep control of his construction site and take responsibility for that,” Gerou said. “I cannot think of an instance where an architect would be held responsible for something that happens at the construction site.”

In Hadid’s case, there is no contractor yet. Though construction on Al Wakrah has begun, the main contractor won’t be announced until spring.

But Gerou says prior knowledge is the exception to the rule of onsite duty: If an architect has “recognized a hazardous condition” beforehand, the ethical norm would be to address it. The numerous reports of worker deaths certainly establishes a precedent indicating more laborers will die before construction is done.

The architect had reason to believe the risks for workers were dire even before The Guardian investigation, for reasons that have nothing to do with the potential complexity of her design. Qatar is one of many Arab countries in the Persian Gulf to practice the labor system known as “kafala.” In this legal arrangement, workers are beholden to employers who oversee their visa applications and legal status. The setup explains why so many workers can’t escape their situation -- employers often hold their passports hostage.

Given the amount of ink shed on kafala in the last decade by organizations like Human Rights Watch, it’s unlikely anyone contracting with the country would be new to the concept or its likeness to slavery (a comparison made even by the Labor Minister of Bahrain, whose country banned the practice only in 2008).

A caveat issued on Hadid’s website after she won the bid last year dances around the issue:

But reality hasn’t worked out according to such neat terms. The new charter Hadid promised has been declared a “sham” by the ITUC, a characterization backed up by the death count. Yet Qatar’s still-brutal conditions aren’t stopping recruits: An average of 20 people every hour are moving to the small peninsula nation, primarily to work on the World Cup, according to a recent Amnesty International report.

Given this grim background, is Hadid still correct in her assertion that she is not responsible for laborers working to make her design a reality?

The crux of this question propels much debate in architecture. Should ethics temper ambition? International architects like Richard Rogers might say Hadid never should have bid for the contract in the first place. “We have a responsibility to society,” Rogers told Dezeen Magazine last year, on the occasion of his 80th birthday. Blaming the dog-eat-dog standards of modern architecture for obscuring that principle, he suggested that professional duty extends “not just to the client but also to the passer-by and society as a whole."

Gerou, the former member of the ethics board for the American Institute of Architects takes a more utilitarian view. “Someone always makes a bid," he said.

With Hadid’s iconic status, she “potentially [has] the power to influence the Qatari government” to make meaningful reforms by speaking out now, Gerou says. For all Hadid’s claims of “no power,” she was crowned one of Time’s 100 most powerful people just a few years ago.

If she wants to take on more duty, Gerou says, she could. “Some matters,” he pointed out, “are up to the architect’s own conscience.”

This is the question facing architect Zaha Hadid, whose Al Wakrah is the most famous of the stadiums rising out of the desert for the 2022 World Cup. Its fame isn’t for the high-profile matches it will host, nor for its size (Al Wakrah is neither the largest nor most critical of the dozen sites for the Qatar games), but for its shape. Though the stadium is meant to reference a traditional Arabic fishing boat, when the designs were revealed last year, everyone from Jon Stewart to the feminist site Jezebel had a chuckle over how much it looks like a vulva.

The notoriety of the design may be why Hadid -- and not, say, Norman Foster or Albert Speer Jr., starchitects who also won World Cup bids -- is enmeshed in a far more serious scandal: a rash of deaths in the name of the tournament.

Hadid -- an Iraqi-born British icon and the first woman to win the famed Pritzker Prize -- is also arguably the best known architect of the bunch. Her stadium is also scheduled to be completed first. While reports indicate that advance construction on her site began in January, it is not known whether any workers have died at Al Wakrah specifically.

Hadid's office did not respond to several requests for comment this week on the World Cup-worker deaths.

According to a recent investigation by The Guardian, since 2012, nearly 900 immigrant workers from India and Nepal have died from circumstances largely related to 2022 World Cup labor. If present conditions persist, up to 4,000 more may die “before a ball is kicked in 2022,” according to the International Trade Union Confederation, which monitors workers’ rights across the globe.

As of last fall, more than half of the dead had succumbed to workplace accidents or heart attacks triggered by the heat of the desert, coupled with squalid living quarters that often drive laborers to sleep on their roofs. One laborer told The Guardian he was physically assaulted by his employer after being forced to work for more than 36 hours on no food.

This in a country so oil rich it’s spending $200 billion on a sports event. That’s $100,00 per capita, versus the $350 per capita lavished on the pricey Sochi Olympic Games, $73 per capita estimated for Brazil’s World Cup, and $54 per capita spent by South Africa when it hosted the tournament (not counting Qatar’s likely hidden costs, in the form of alleged bribes to win the bid in the first place.)

“The overall picture is of one of the richest nations exploiting one of the poorest to get ready for the world's most popular sporting tournament,” The Guardian report concludes.

How does Hadid fit into this mess? By claiming she doesn’t.

The architect drew outrage and criticism last week when she told The Guardian that she has “nothing to do with the workers.”

“I think that's an issue the government –- if there's a problem –- should pick up,” she added. “Hopefully, these things will be resolved … It's not my duty as an architect to look at it … I have no power to do anything about it."

She wasn’t helped by that qualifier -- “if there’s a problem” -- the casualness of which hardly relayed caution or concern. Hundreds of deaths is certainly a problem. The backlash has been widespread, and the headlines rough: “Zaha Hadid Is An Awful Human Being,” starts one, on the art world news site Hyperallergic.

But is Hadid correct?

According to architect Phillip H. Gerou, yes, technically speaking. Gerou, a past member of the ethics board for the American Institute of Architects, told The Huffington Post that architectural ethics codes typically ascribe the “duty” of caring for worker safety to the contractor.

“The contractor necessarily needs to keep control of his construction site and take responsibility for that,” Gerou said. “I cannot think of an instance where an architect would be held responsible for something that happens at the construction site.”

In Hadid’s case, there is no contractor yet. Though construction on Al Wakrah has begun, the main contractor won’t be announced until spring.

But Gerou says prior knowledge is the exception to the rule of onsite duty: If an architect has “recognized a hazardous condition” beforehand, the ethical norm would be to address it. The numerous reports of worker deaths certainly establishes a precedent indicating more laborers will die before construction is done.

The architect had reason to believe the risks for workers were dire even before The Guardian investigation, for reasons that have nothing to do with the potential complexity of her design. Qatar is one of many Arab countries in the Persian Gulf to practice the labor system known as “kafala.” In this legal arrangement, workers are beholden to employers who oversee their visa applications and legal status. The setup explains why so many workers can’t escape their situation -- employers often hold their passports hostage.

Given the amount of ink shed on kafala in the last decade by organizations like Human Rights Watch, it’s unlikely anyone contracting with the country would be new to the concept or its likeness to slavery (a comparison made even by the Labor Minister of Bahrain, whose country banned the practice only in 2008).

A caveat issued on Hadid’s website after she won the bid last year dances around the issue:

All construction contracts for the stadium will be issued in line with the Qatar 2022 Supreme Committee’s Workers’ Charter and Standards -- developed in consultation with international human rights organizations -- which will enforce best practice, in line with the government’s vision for worker welfare, and cement the tournament as a catalyst to the improvement of workers’ welfare within Qatar and the region.

But reality hasn’t worked out according to such neat terms. The new charter Hadid promised has been declared a “sham” by the ITUC, a characterization backed up by the death count. Yet Qatar’s still-brutal conditions aren’t stopping recruits: An average of 20 people every hour are moving to the small peninsula nation, primarily to work on the World Cup, according to a recent Amnesty International report.

Given this grim background, is Hadid still correct in her assertion that she is not responsible for laborers working to make her design a reality?

The crux of this question propels much debate in architecture. Should ethics temper ambition? International architects like Richard Rogers might say Hadid never should have bid for the contract in the first place. “We have a responsibility to society,” Rogers told Dezeen Magazine last year, on the occasion of his 80th birthday. Blaming the dog-eat-dog standards of modern architecture for obscuring that principle, he suggested that professional duty extends “not just to the client but also to the passer-by and society as a whole."

Gerou, the former member of the ethics board for the American Institute of Architects takes a more utilitarian view. “Someone always makes a bid," he said.

With Hadid’s iconic status, she “potentially [has] the power to influence the Qatari government” to make meaningful reforms by speaking out now, Gerou says. For all Hadid’s claims of “no power,” she was crowned one of Time’s 100 most powerful people just a few years ago.

If she wants to take on more duty, Gerou says, she could. “Some matters,” he pointed out, “are up to the architect’s own conscience.”